One of Tom Doughton’s most popular courses was Worcester: Insiders and Outsiders. In a way, it summed up his life’s work.

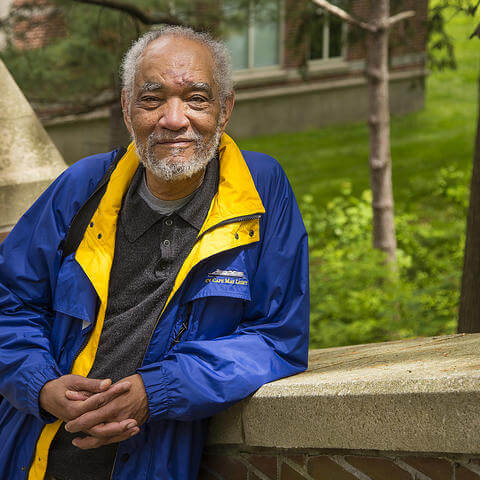

It is hard to imagine a person more outside the mainstream than Holy Cross senior lecturer Thomas Doughton, who died Feb. 3, 2024, at the age of 75. Tom was Black, Native American and queer. He was a scholar of American history and Holocaust studies.

As a historian, Tom focused on the lives of people outside the dominant histories — Native and Black Americans, especially of the Worcester region, whose contributions, dwellings, customs and occupations had gone largely unrecorded. He brought these lives and stories into the mainstream and into the larger public record through his numerous public lectures, interviews and essays; his co-edited collection of Worcester Slave Narratives, “From Bondage to Belonging”; his leadership in the creation of Worcester’s Black History Trail; and his film about the Native American identity of the region — including Holy Cross’s particular place in it — “Pakachoag: Where the River Bends" (below).

Tom’s vocation as a historian was one of recovery: he lived to tell the stories of people whose lives had been, in his terms, “erased,” or appropriated and romanticized. His aim was “to get control of our stories.” He did painstaking work to follow family trees and physical movements of native and Black people in the region (their family trees often intersected), to find deeds of properties they owned, the wills they made, the violins and eyeglasses they left behind. Tom literally marked their lives on the landscape by creating the Worcester Black History Trail in 2023, with its impressive markers that repeople local streets by saying the names, addresses and occupations of Black residents who lived there.

Tom’s place-marking strategy derived in part from his study of the Holocaust and the placement of “Stumbling Stones” in Germany to mark where Jews lived, those later deported by the Nazis to concentration camps — the names physically put back in the place from which the living people had been erased. The Black History Trail markers call us to stop and remember the people who lived, married, worshiped and worked here — to see how the city we inhabit is one they helped build.