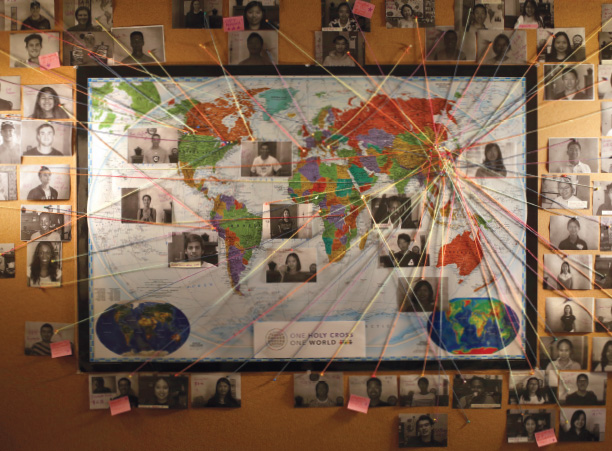

Holy Cross Office of International Students, a map that includes photos of dozens of young people with lines connecting them to their home countries. Two of those lines connect faces to a place that some would believe most unlikely to produce students capable of thriving at an American college or university: Somaliland, a poor country on the Horn of Africa that has yet to gain international recognition after breaking away from Somalia more than 25 years ago.

Sahra Hassan ’19 and Zak Muse ’19 came to Holy Cross after studying at the Abaarso School of Science and Technology in Somaliland. Abaarso itself is an unlikely place, a boarding school for students in grades seven to 12 begun by an unlikely educator, a young former hedge fund manager who grew up in Worcester, just a few miles across the city from the College of the Holy Cross.

That educator, Jonathan Starr, envisioned a school teaching bright young students, sending them abroad to college and having them return to become leaders who would shape the future of their country.

Hassan and Muse, both 21, are well on their way to fulfilling Starr’s vision. They are determined to make the most of their college experiences, move home after graduation and apply their knowledge and perspective to the challenges of a country that desperately needs improvements in education, transportation, energy and sanitation.

This map of the world in the Office of International Students displays photos of students with yarn connected to their home countries. There are 100 international students currently studying at Holy Cross. Photo by Tom Rettig

This map of the world in the Office of International Students displays photos of students with yarn connected to their home countries. There are 100 international students currently studying at Holy Cross. Photo by Tom RettigThe Abaarso School

Starr’s mother, Susan, describes her son as an unusual boy who became an unusual man, an out-of-the-box thinker, “intellectually obsessive,” even as a child. His interests evolved from tropical fish, to football, to basketball as a youth and to philosophy and then finance in college.

After a stint as a research associate in the taxable bonds division of Fidelity Investments, Starr, at just 27, began a hedge fund in Boston, Flagg Street Capital, which was named after his elementary school in Worcester.

But he enjoyed the theory of finance more than its practice and, despite his wealth and success, he closed the hedge fund.

“Ultimately, I was just interested in doing something else,” he says. “Chapter over.”

Starr got the idea for a school during a two-week visit to Somaliland with his uncle, a native of the country. He said it was hard not to get caught up in what he called Somaliland fever, fed by the friendliness and peacefulness of its people, in contrast to the stereotype of Somalia as a haven for Islamic radicalism.

The Abaarso School campus, located just outside of Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in northeast Africa. Photo courtesy The Abaarso School

The Abaarso School campus, located just outside of Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in northeast Africa. Photo courtesy The Abaarso SchoolStarr knew nothing about starting a school, but he suspected he’d be good at running a nonprofit business with a mission he believed in. He also had money — he poured $500,000 of his own into the school — and had yet to start his own family.

“I thought this was the best chance I might ever have in my life to do something really special,” he says.

While the decision to start a school came easily, acceptance among the locals did not. Starr compares his effort to aliens landing a spaceship, building a beautiful school and saying, “‘Hey, bring your children here.’ Naturally, you’re going to be a little skeptical.”

Besides the skepticism, there were those who did not want to see the school succeed, including people who profited off the existing school system. But Starr persevered, and the school opened in 2009. He recruited young, idealistic Western teachers who bought into the mission and were willing to work for $3,000 a year in a school surrounded by a wall with barbed wire and guarded by armed men.

Public perception of Abaarso changed when its first students got scholarships to American colleges.

“It was so beyond anything they thought was possible,” Starr says of the locals’ acceptance. “We didn’t win by bribing people. We didn’t win by lying. We won because our students were so good. Our students won. That’s what changed it.”

Besides English, the school teaches math, creative arts, history, Islamic studies, science and computer science. Tuition is $1,800 a year. Students whose families cannot afford that rely on financial assistance, including full scholarships. More than 100 former Abaarso students are studying at schools abroad, including Harvard, Yale, MIT — and the College of the Holy Cross.

Welcoming International Students

Tina Chen, the director of the Office of International Students, says Holy Cross has steadily increased the number of international students it accepts and enrolls in recent years, going from six in 1993-1994 to 64 in 2016-2017. The unofficial number for the current school year is about 100.

Part of the mission at Holy Cross, Chen points out, is to prepare students to be leaders and world changers, people who will shape the future.

“To do that without attention to the global environment in which we live would be foolhardy,” she says, adding that international students enrich the campus community with their perspectives and experiences, much as women and people of color did when their numbers began increasing decades ago.

Hassan and Muse came to the attention of Holy Cross after College President Rev. Philip L. Boroughs, S.J., began a push to enroll more international students — students from all kinds of backgrounds, including those unable to pay — for exactly that reason. Drew Carter, senior associate director of admissions, served on the committee working on that initiative, building relationships with schools and other organizations to find matches that would be good for students and good for Holy Cross.

“Literally out of the blue at that time, I met Jonathan Starr,” who was looking for schools for Abaarso students, Carter says. “It really was wonderful timing.”

Jonathan Starr, founder of the Abaarso School, on campus at Holy Cross. Photo by Tom Rettig

Jonathan Starr, founder of the Abaarso School, on campus at Holy Cross. Photo by Tom RettigBoth were prepared academically, and Hassan had spent two years after Abaarso at a girls’ boarding school in Connecticut, which eased her transition to Holy Cross. Muse took a different route, coming directly from Somaliland after meeting with Carter via Skype.

“He had grit and grace,” Carter says. “I really felt he would be successful here at Holy Cross and that Holy Cross would benefit from him being here.”

“We make our best efforts to have the freshman class resemble the outside world,” Carter says. “Zak and Sahra are at the forefront of those efforts.”

Acclimating to the U.S.

Susan Starr, mother of Abaarso School founder Jonathan Starr, (second from right) acts as a surrogate mother to many of the Abaarso School graduates studying in the U.S. Here, she hosts several at her house in Worcester. Photo by Tom Rettig

Susan Starr, mother of Abaarso School founder Jonathan Starr, (second from right) acts as a surrogate mother to many of the Abaarso School graduates studying in the U.S. Here, she hosts several at her house in Worcester. Photo by Tom RettigSusan Starr, who serves as an unofficial mom to many of the Abaarso students studying in the U.S., recalls asking him,

“So, what do you think of the country so far?”

And he answered, “I didn’t come to a new country, I came to another planet.”

One of nine children, he was raised by his mother after his father died when Muse was an infant. His mother got up at 4 a.m. to sell meat to neighbors to support her children, and later his oldest brother worked to help provide for them. Muse is the first of his siblings to attend college.

His mother, who never went to school, valued education for her children and saw it as a path to opportunity for them. Muse remembers her calling him the “Sultan of Africa” as a child, believing that education could help him achieve just about anything.

He went to an Islamic school and primary school before taking the highly competitive exam for Abaarso.

“It was like the best thing that ever happened to me,” he says of getting into the school and the education he received there.

Not that it was easy. Abaarso is an English immersion school, and Muse initially found it hard to communicate with his teachers - except in math class. “Math I understood because it was numbers,” he says.

At Holy Cross, he’s majoring in mathematics and hopes to enter into a Holy Cross partnership with Columbia University to study chemical engineering. This past summer, he took a class and worked in Dinand Library.

Muse plays down his obvious intelligence. “They think I’m extremely smart, but I’m just lucky, you know? I’m just a lucky kid.”

And an appreciative one. Jonathan Starr tells of sharing a meal at Holy Cross with him, when Muse looked around and commented on his surroundings and the selection of food. “You know, it will be a shame if there’s ever a time when I don’t appreciate this.”

Muse says the College’s emphasis on high intellectual and ethical standards are helping make him the person he needs to be in the generation that will help transform his homeland.

Challenges Lead to Growth

Hassan, like Muse, came from a large household, even though she just has one sibling, a younger sister. In Somali tradition, she grew up among aunts, uncles and cousins, 13 people in all. Their home was busy, and loud.

“There was always someone saying something,” she says with a laugh. “You had to be loud to be heard.”

Her father worked for the World Health Organization and her mother for UN-Habitat, a United Nations settlement and development program, and it was a given that she and her sister would go to college. “It was expected in our household.”

But before she got there, she went to primary school, middle school and Abaarso in Somaliland and the Westover School, an all-girls boarding school in Middlebury, Connecticut.

She chose Abaarso because her parents felt it would lead to greater opportunities and because of the promise from the school that it would do everything possible to help her further her education.

“I would not be where I am today if I went to a different school,” she says.

Was it hard? “Oh, God, yes,” Hassan says. The school day began at 7 a.m. and ended at 10:15 p.m., after classes, community service, sports and study time. English immersion was particularly difficult.

“I didn’t know what they were saying for the first couple months,” she says, “but all of us were in the same boat.”

At Holy Cross, Hassan is studying international studies and social justice. Last summer, she helped organize the Jesuit Universities Humanitarian Action Network (JUHAN) conference hosted by Holy Cross and completed an internship at Community Legal Aid, a free law office, writing the script for a commercial to promote the federal food assistance program and lessen its stigma.

She has found Holy Cross challenging and rewarding. “I’m more engaged in who I am and the place that I’m at today,” she says.

“At Holy Cross, I learned to ask myself questions like, ‘Who Am I?’ ‘What am I passionate about?’ and ‘Who will I be for others?’ ”

Hassan is still looking for those answers, but knows the quest to answer them will serve her well.

“The education, mentorship and support I continue to receive from Holy Cross have helped me find my love and passion for social justice, and I want to be part of mission-driven work that serves others when I return home.”

The Travel Ban

Hassan and Muse faced one challenge most other international students didn’t have to worry about: the Trump administration travel ban. That executive order, which targets six mostly Muslim countries and is pending before the Supreme Court, had left students from those countries, including Hassan and Muse, in limbo. That’s because Somaliland is not recognized and is considered part of Somalia, one of the six countries affected by the ban.

Hassan and Muse feared if they went home, they would not be allowed to return to school in the U.S. And they were concerned that future students from their country would not be allowed to come to the U.S. at all.

The high court, while deciding to hear the travel ban case in October, did say in late June that people from the six predominantly Muslim countries could come to the U.S. if they had “bona fide relationships” here, including with schools. That would seem to lift the ban, at least temporarily, on students, although some uncertainty remained.

Hassan wants future students to have the same chance she and Muse have to study in the U.S.

“I have been privileged to get that opportunity, but I’m hopeful for other students who have the skills, who worked hard, who did what they were told to do to get to the United States, to be able to get that opportunity also.”

Forming Future Leaders

Jonathan Starr now lives in Westborough, Massachusetts, with his wife and 2-year-old daughter. They are expecting a second child in September. But he’s far from settled. While he has turned over headmaster duties at Abaarso, he continues development work on behalf of the school, including fundraising, getting its students into prep schools and colleges abroad, troubleshooting for students in the U.S. and finding internships for them.

He describes himself as addicted to progress, someone who finds it hard to relax, someone who continually asks himself, “What did I advance today?”

But he takes great satisfaction that his vision for Abaarso and its long-term impact on Somaliland is coming into focus eight years after he began the school. Its first graduates, who returned to Somaliland, will be teaching, some at Abaarso and at least one at a women’s university that Starr and another former assistant headmaster at Abaarso, Ava Ramberg, have founded in Hargeisa, the country’s capital.

Students in grades 7-12 are enrolled at Abaarso, with approximately 50 students per grade, divided evenly by gender. Here, some of the female students gather between classes. Photo courtesy The Abaarso School

Students in grades 7-12 are enrolled at Abaarso, with approximately 50 students per grade, divided evenly by gender. Here, some of the female students gather between classes. Photo courtesy The Abaarso SchoolWhen Hassan returns to Somaliland, she wants to work for a nonprofit before deciding about graduate school. Muse says he’d like to teach and otherwise contribute to the community, though he has no definite plans.

Both feel pressure to meet expectations about becoming future leaders of their country, but, as Muse put it, “That’s not bad.” The opportunity inspires them.

“It’s time for us to be self-sufficient,” Hassan says. “It’s time for us to do it for ourselves.”

Muse agrees. “My dream goes way beyond Somaliland. I want to see an Africa that perceives its potentials as the tools to become the next super power. The growing democracy, the demographics, and the environment are all inspiring factors that are in our favor. But for that to happen, we first need great leaders, and that is what this next generation of Africa is all about.”

Written by Dave Greenslit for the Fall 2017 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.