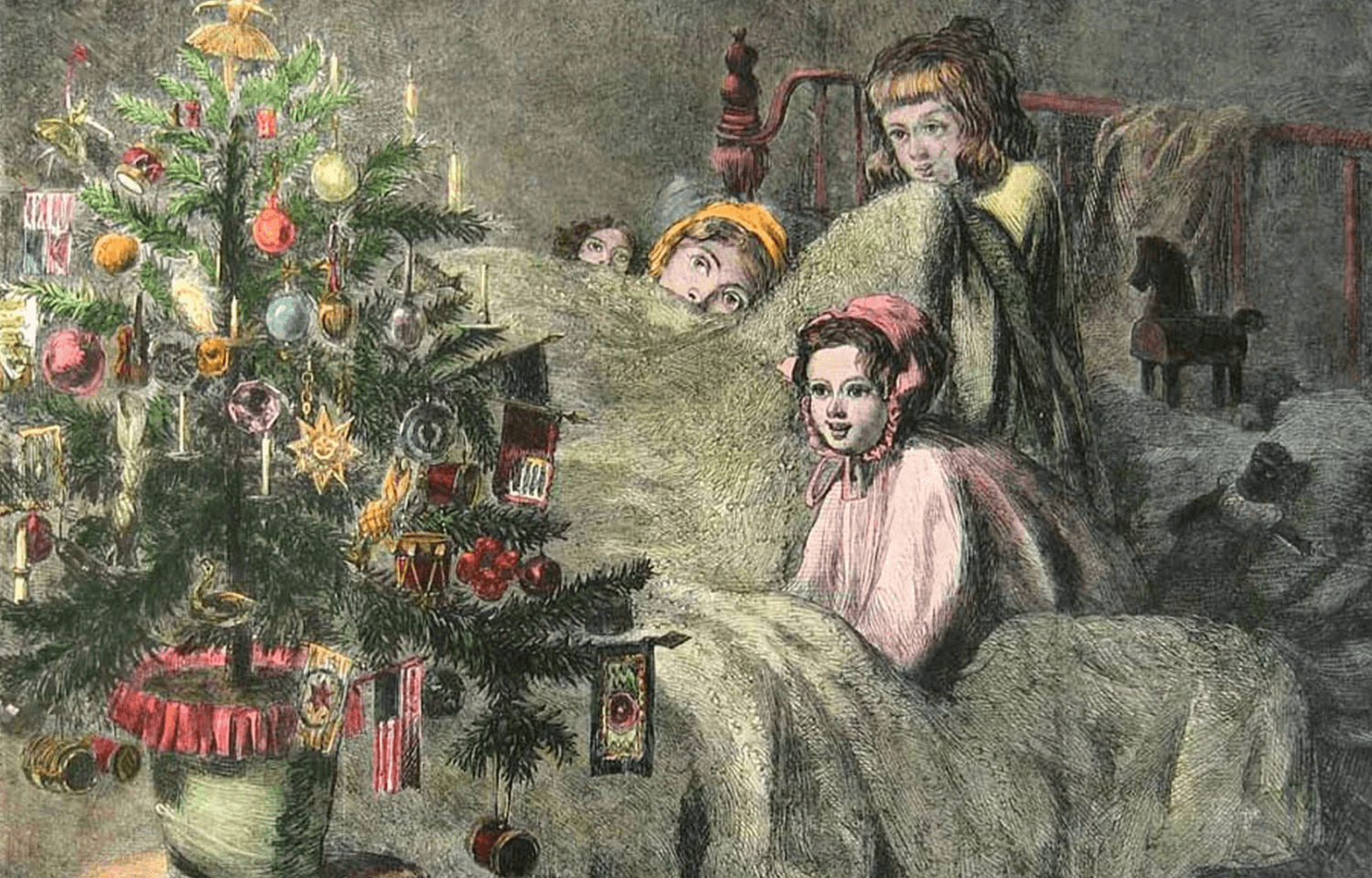

Before Halloween held the monopoly on all things spectral, the telling of ghost stories was the principal entertainment for Europeans at Christmas time. Some suggest that the tradition grew out of Winter Solstice celebrations, but it is impossible to affix a date to an oral tradition.

What is not in question is who gets the credit for the most famous Christmas ghost story ever written. That honor goes to English novelist Charles Dickens, who wrote “A Christmas Carol” in 1843. The initial print run of “A Christmas Carol” (6,000 copies) sold within days of its December publication.

Debra Gettelman, associate professor of English, teaches courses on Dickens and Dickensian fiction. Speaking on the enduring power of “A Christmas Carol,” Gettelman underscored the social justice themes in his work, which appear even in his ghost stories.

“Dickens’s whole orientation was towards using fiction to move readers’ hearts and minds to care about the poor,” she said. “His was a moment when there was no social safety net.”

Midway through the 19th century, England had industrialized ahead of the rest of the world. “And so there’s this rampant, unrestricted capitalism creating this enormous gap between rich and poor with no social safety net at all. No child labor laws, nothing,” Gettelman said.

What to read this Christmas

For those looking to revive the tradition, here are a few other recommendations for a ghost story at Christmas.

Seeking, no doubt, to capitalize on his readership’s appetite for yuletide fright, Dickens produced subsequent Christmas ghost stories, “The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain” (1848), “A Christmas Tree” (1850) and “The Signalman” 1866.

Susan Elizabeth Sweeney, distinguished Professor of Arts and Humanities, assigns students both Dickens's “A Christmas Carol” and "A Christmas Tree" in her course Ghost Stories. Study of ghost stories sparks lively discussions, Sweeney said.

Of "A Christmas Carol," Sweeney said: "We enjoyed debating whether the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future can be considered ghosts -- like Marley's Ghost -- as well as the extent to which all fictional phantoms are related to the passage of time."

In “A Christmas Tree,” Sweeney notes, Dickens includes a kind of literary tip of the hat to the tradition.

“There is probably a smell of roasted chestnuts and other good comfortable things all the time, for we are telling Winter Stories — Ghost Stories, or more shame for us — round the Christmas fire; and we have never stirred, except to draw a little nearer to it,” Dickens writes.

And what of the tradition on this side of the Atlantic? The Puritans didn’t go in for ghost stories at Christmas, forsaking folklore and the supernatural. One American did take up the tradition, however. Henry James’s 1898 novella "The Turn of the Screw" received mixed reviews from critics upon publication, for its subject matter. Spoiler alert: The protagonist, a governess, kills one of her wards, maybe because of malevolent ghosts, maybe because of psychological distress. Some critics found the tale abhorrent, but the book has become a classic, credited with introducing readers to the concepts of psychological horror and the unreliable narrator.

That is, unless the governess is to be believed. In which case, her defense is a variation on a very old theme: The devil made me do it.

Guilty or innocent? James leaves it to the reader to decide, but what is abundantly clear from the very first sentence is that his is a story best told at a particular time of year:

“The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas eve in an old house, should essentially be, . . .”