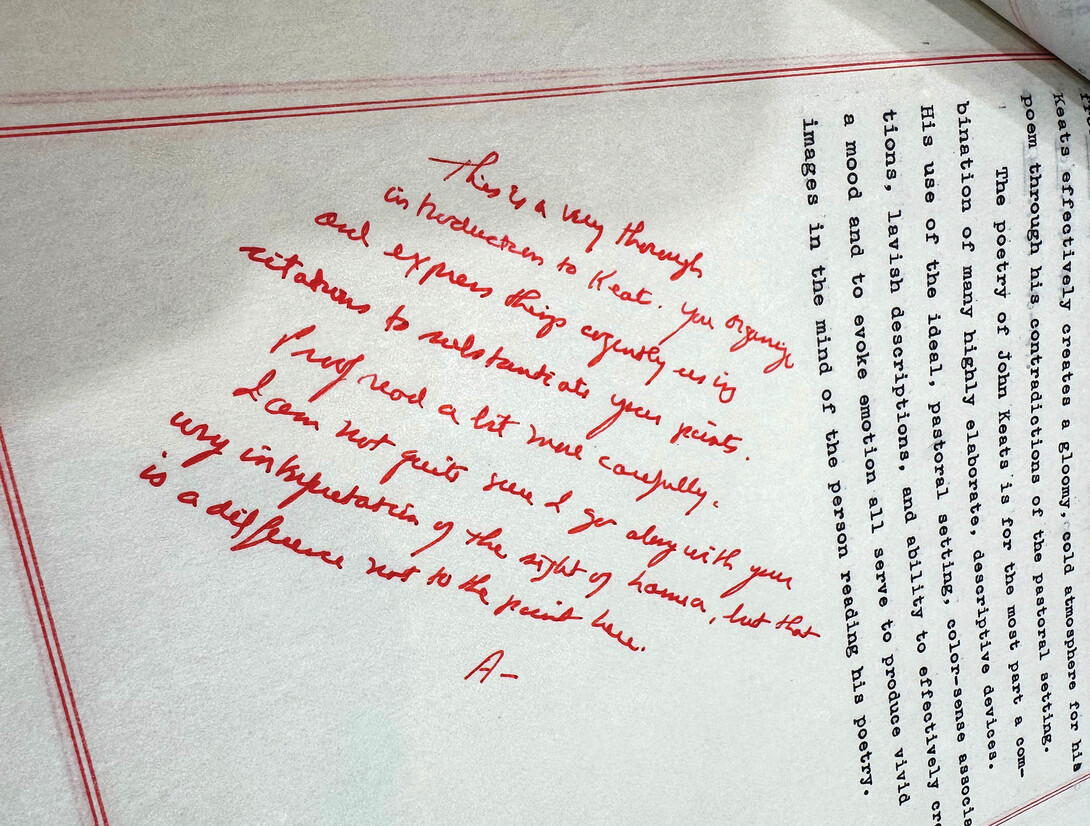

Peter Hogenkamp, M.D., ’86, was a chemistry major looking to have “the Callahan experience” when he enrolled in Survey of Irish Literature in his senior year: “I’m pretty sure I was the only non-English major, and I think Professor Callahan appreciated the fact that I would give my direct, unadulterated opinion on the reading.”

Callahan’s rejoinders would begin with a deliberate misremembering of his name: “Häagen-Dazs,” “Hogenkaeze,” “Hogenkrieg,” followed by variations on a theme: wrong.

Example: “I have been teaching this poem for over 30 years, Herr Hogenkamp, and that is the first time I have ever heard that opinion. Unfortunately, Herr Hokenkrieg, originality doesn’t always imply genius.”

It was great training for medical school, Dr. Hogenkamp says. “I had this internal medicine rotation led by this great teacher, but he would always try to trip you up, make you uncomfortable, etc.,” he recalls. “His whole point was that you have to be ready to defend yourself, to cite references, to stand your ground. Ed’s class stood me in good stead. His example has helped me throughout my entire career.”

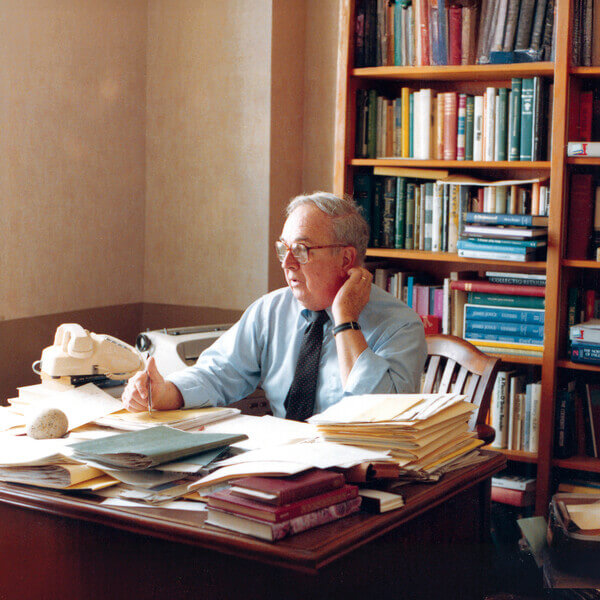

During a 2025 visit to the College, another of Callahan’s former students, Anthony Fauci, M.D., ’62, Hon. ’87 said, “I had a great affinity for him and his class because of the way he approached the English language. Precision of thought and economy of expression. His favorite thing was when someone would come into class and start talking and the person would go in 16 different directions, and Professor Callahan would say, ‘You really would be much more effective if you communicate to me one precise thought that I can get my arms around and, importantly, say it in as few words as possible as we don’t have a lot of time.’ I’ve brought that mantra with me throughout my entire career in something that is far removed from English literature; namely, in presenting an interesting scientific or public health concept to people, I’ve used the same approach.”

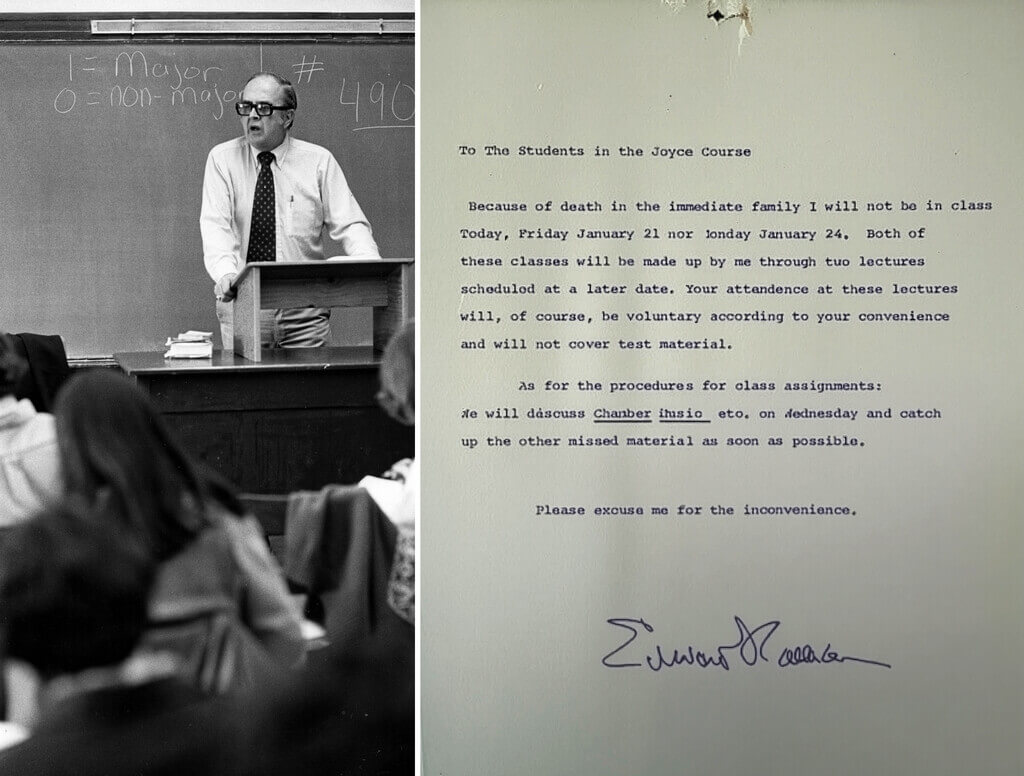

Another lesson former students recall with regularity: Absenteeism would not be tolerated.

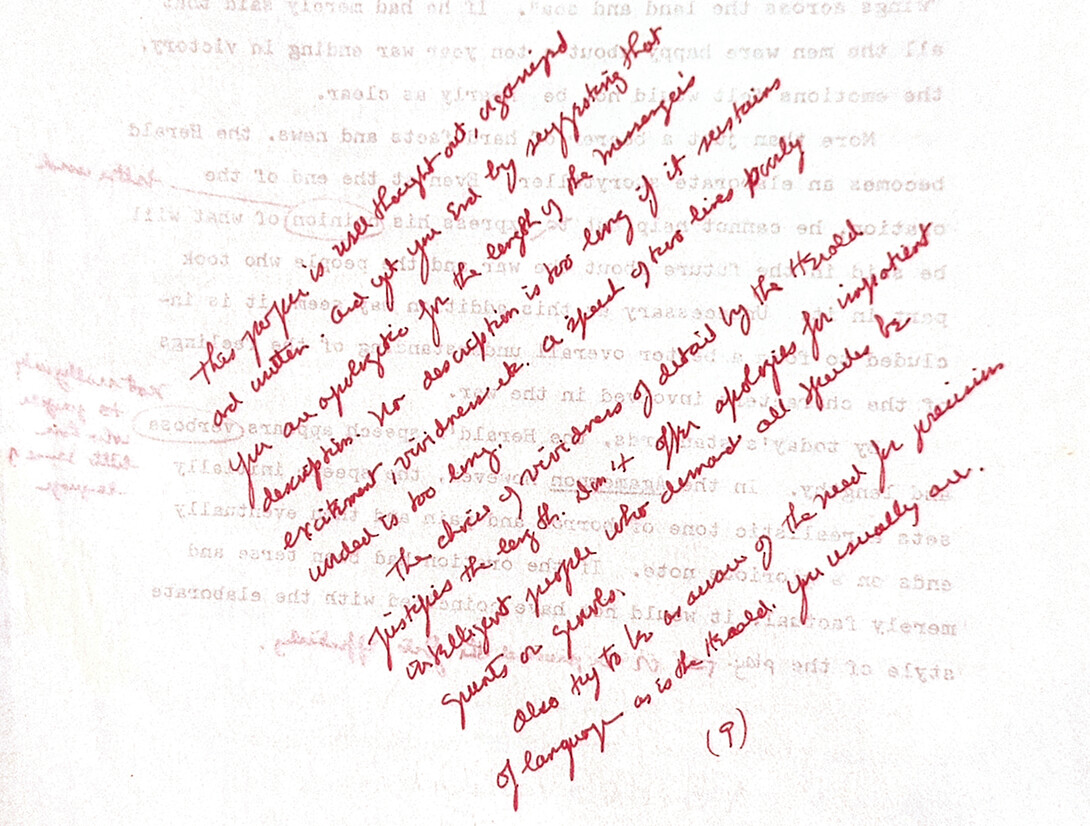

In a 1983 syllabus from Callahan’s Joyce seminar, that hallmark combination of humor and seriousness is brought to bear on his absenteeism policy:

“Under no circumstances will absentee examinations or late papers be accommodated. In the case of a student missing an hour examination because of serious reasons, he will be allowed the opportunity of demonstrating his mastery of the material by submitting a lengthy (35 pp.) term paper on a subject determined by the instructor.”

Put another way (as he did in his Joyce seminar in the fall of 1987): “The only reason to miss this class is death (long theatrical pause) as in yours.”

“He once called a student who’d missed class twice to ask him when the funeral was,” Colin Callahan says.

J. Michael Joyce ’79 is such a fan of his former professor that he shelves his “Riverside Shakespeare” — “with all my notes in the margins” — next to his Bible. And yet, Joyce, albeit reluctantly, once tested Callahan’s resolve.

“I was the best man at my Uncle Tim’s wedding and I had to get down to New York City at some point on a Saturday,” Joyce shares. “I said to Tim, ‘I’ve got a Shakespeare exam that morning.’ Tim says, ‘I took Callahan; just tell him it’s my wedding and see if you can take it a day earlier.’

“So, of course, I walk in with my head down and ask and he said no,” Joyce continues. “He said, ‘When’s the wedding?’ I said, ‘Probably, 3 or 4 in the afternoon in New York.’ He said, ‘Fine. It takes three hours to get to New York City. We’ll figure this out. Be in my office at 8 o’clock Saturday morning. You’ll be done by 11 and can be in a car by 11:15 and on your way.’ Which is what I did. He would not show favoritism under any circumstances. I just think he wanted everybody to play by the same rules.”

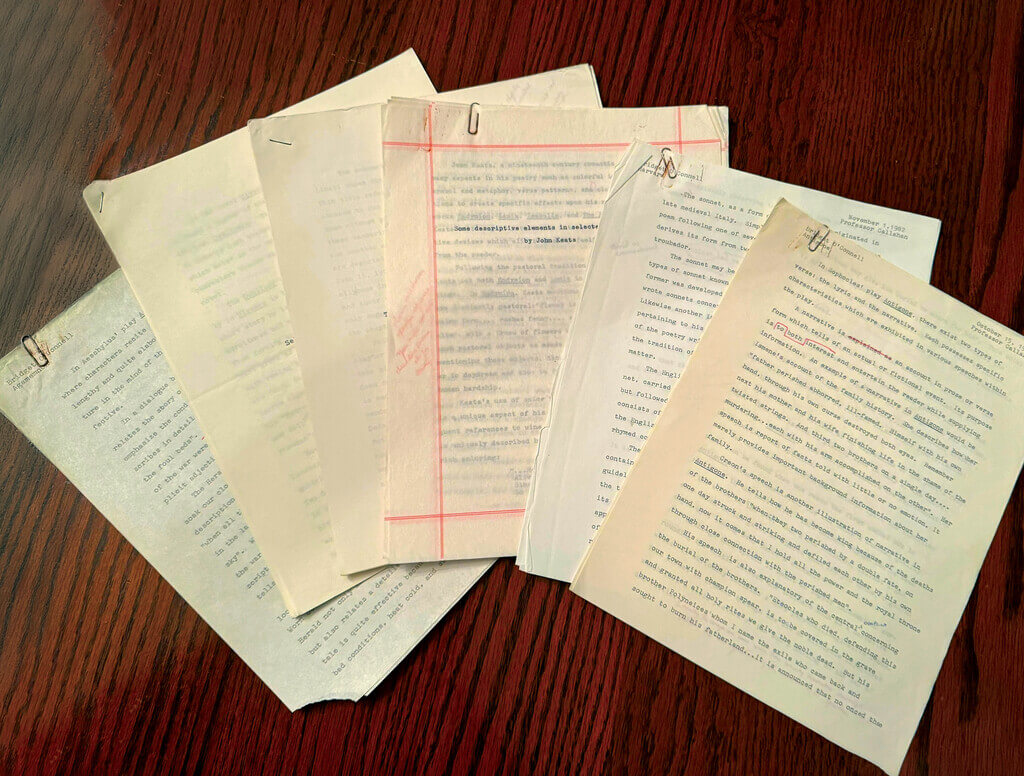

Callahan expected punctuality and perfect attendance in his classes. If he had to cancel class, students might receive a formal notice.

A request for memories of Callahan prompted many alumni to share stories of how his example spurred them on to careers as high school English teachers and professors, some ascending to the heights of their profession, such as American medievalist Traugott Lawler ’58, professor emeritus at Yale University, authority on Chaucer and English poet William Langland, and author of the books “The Penn Commentary on Piers Plowman, Volume Four,” and “The One and the Many in The Canterbury Tales,” among others. Lawler, along with classmates Michael O’Loughlin, John Wilson and Art McGuinness, all earned Ph.D.s and taught college English (Wilson at Holy Cross). Lawler says all four friends held their professor in the highest regard in matters of literature and life.

“Ed had joie de vivre. He definitely had joie d’enseigner (love of teaching), he just loved teaching, but he loved every other part of life, too,” Lawler says. “His urging me to marry, young though I was, came from that — and here we are, Peggy and I, in our late 80s, happily moving toward our 67th anniversary.

“He has been a model of good teaching and wise living for me through my whole life,” Lawler says. “I feel lucky to have known him.”

Peter Merrigan ’88, CEO and managing partner of Taurus Investment Holdings LLC, established the Professor Edward Callahan Irish Studies Support Fund more than 20 years ago. Like Lawler, Merrigan found a mentor in Callahan.

“If you took one of his classes, you knew you were taking the hardest subject matter with the most talented professor on campus,” Merrigan says. “It wasn’t easy — you were taking apart ‘Ulysses’ after all — but he made it seem that that was something you could do.”

As graduation neared, Merrigan, uncertain about what he wanted to do in life, sought Callahan’s counsel: “I was spinning around in my own head. Should I be a lawyer? Go back to school? And he simplified things for me, helped me dissect my own life. He asked me, ‘What gets you up in the morning that you’re excited about?’ And I always liked building things, taking things apart and rebuilding them.”

Callahan’s counsel cleared his head, Merrigan says: “That conversation, I kind of equate it with his teaching style. He could take a complicated problem and make it understandable. That was his gift.”