After my oldest son graduated from Holy Cross in 2006, he taught at the Nativity School in Worcester. At that time he asked me, both with some gentle sarcasm (since he truly did not want another long-winded answer from a father who talked way too much about education and teaching) and with some genuine interest, how I would answer this question: If you could boil down all your years of teaching into one sentence of advice, what would it be?

I said, “Love your students.” I knew discipline, likeability, dedication to the job would follow if the students he taught knew he had them in his heart — not just their best interests but their very well-being, the possibilities of what a good life might look like. I didn’t mean, and he knew me too well to think I would, some kind of mushy-aren’t- you-wonderful kind of love.

Loving is hard work. It asks you to be vulnerable, to allow students into your life, because you don’t only teach the subject matter you fell in love with, you also teach your own life. What did I live for? Why did I care about the books I taught? I wanted my students to know my own multiple answers to such questions. And I wanted them to ask questions that would personalize a literary work for them: What does this book mean to you? Is there any passage or idea that would change your life or your idea of what your life should be? Is there anything at all in what you read that could help you become more fully human? Why should you read this book at all?

Years ago, I asked myself: Why do I teach? My answer then, and it would be the same now: I wanted my students to “taste and see,” as the Psalms put it, the surprise of such a thing as being at all. And I wanted to do so together, believing that at any moment such surprise could happen to us, together in a classroom on a late afternoon.

In the back of my mind, I always heard the voice of a colleague, Clyde Pax, who once asked at a college-wide meeting on curriculum, “Why don’t we teach the students how to mourn? Isn’t that as important as biology or English or any other discipline?” Clyde was only half-joking. He knew that our job as teachers was to help our students live the fullest possible lives. At the end of his teaching career, Clyde taught in a room next to where I was teaching. We often walked back to Fenwick together. He suffered every time he thought he’d failed to make an idea live for a student, to make what they read and thought part of their lives. That suffering was an act of love. Why did Clyde choose mourning that afternoon so long ago? Because he knew that part of teaching was helping his students to face life fully, both its joys and its sorrows. If philosophy (what Clyde taught) couldn’t do that, then the discipline was nothing more than the study of a history of ideas: fleshless and unanimating.

Three years ago, I had a cardiac arrest. I was dead, then I was alive again. Six years ago, my middle son, Daniel, died. Since those events, I have been thinking a lot about my life, the bulk of which I spent teaching. I have no doubt that I affected many lives over my years at Holy Cross and, later, at Seattle Pacific University teaching poetry to MFA students. But did I help my students live fuller lives, did I help them face suffering and grief? Did they know how much they allowed me to be my best possible self? Could they see, as I saw, that I became less and less judgmental of them over time? That they taught me how to be less judgmental? In my last year of teaching at Holy Cross, a student pointed out that someone in the class was missing most of the classes. When the student wanted to know why I wasn’t angry, how the missing student was to be punished, I answered: If I get angry at him, I will lose any chance I have of helping him. At the end of my teaching life, I thought only about what I could say that might provide a new beginning for the student and myself. Perhaps I should have added when I said “love your students” to my son, that they would also teach him how to love.

I often said to my students that gratitude was the foundation of my life. That we live in a world that need not be, but is. That life is both a mystery and mysterious in the way it is intelligible to us. That without gratitude, finally, there is no possibility of happiness or contentment. My students helped me live gratefully. Even after my son’s death, when gratefulness was difficult, at times impossible, I could return to the years I got to spend with students at that time in their lives when the biggest questions of life are quiveringly alive in them. And each time my thoughts of them helped me remember how lucky I was. And for that I will always be grateful.

Late Valentine from an Old Teacher

Forty years of teaching and then

the inevitable last class. I had nothing

new or remarkable to say. I taught

what was on the syllabus, held back

the emotions of the moment.

Like most everything in life, I’d like

another shot at it. What would I say?

I’m no wiser. I don’t have any desire

to salvage some essential truth

from the junkyard of old truths.

No, I’d just like you to know how lucky

I was to teach you, your honest love

of questions buried under the confusions

of who you were and who you wanted to be.

And thank you for making me

less self-absorbed, for needing me enough

to wait outside my door. I apologize

for those times when I did not know

what you needed from me. And I’m sorry

I tired of trying to re-create the thrill

of what mattered to me part of your lives.

Of course you were more interested

in each other than me. I never minded.

But now, years later, I need to say

what you probably guessed (how else

could I have done the job so long?) —

say it, directly: I loved you all,

even the ones who missed class,

or didn’t do the work, or thought

the rewards of literature were trivial

at best. You, too, taught me

to forget myself, to wait for you to find

what you needed. I learned to attend

to your silliest needs because just then

they were monumental to you.

There’s more: I loved to sit with each of you

in that timeless day-after-day, the seasons

changing around us as we talked on and on

as if we could unencumber each other’s lives.

To me, years away now from that last day,

you are dressed in light, my shepherds

herding me gently out the door.

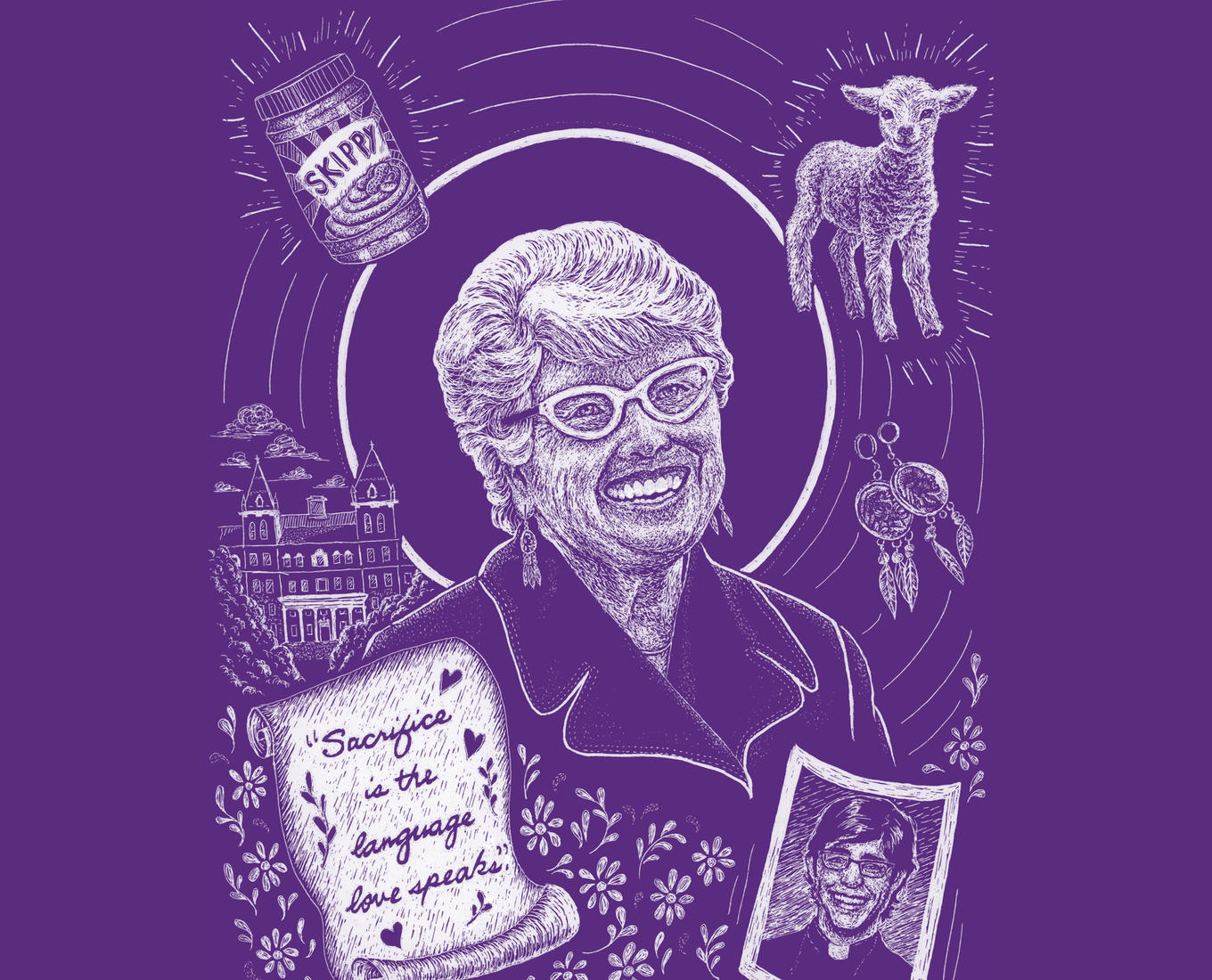

Robert Cording, professor emeritus of English, taught at Holy Cross for 38 years and served as the Barrett Chair of English in Creative Writing. He has published nine collections of poems and, following his retirement, worked for five years as a poetry mentor in the Seattle Pacific University low-residency MFA program.