Cummings and Facebook group member Dolly Griffin talked about hosting a party for Hodgkin survivors, “sort of like a wedding reception, but with no one getting married,” she notes. Cummings flew to Texas to meet with Griffin to plan a party and ended up founding an organization — Hodgkin’s International — instead.

“We discussed how often in the Facebook group people shared about the symptoms they weren’t getting answers to, about doctors who pooh-poohed their concerns,” Cummings says. They decided they needed an organization to not just support survivors, but also to educate them because they weren’t getting information elsewhere.

“Erin instinctively knew what survivors needed,” Rich Cummings says. “Starting Hodgkin’s International was clearly a passion and a calling.”

According to the organization Children’s Cancer Cause, more than 95% of childhood cancer survivors will have a significant health-related issue by the time they are 45, yet many patients, their parents and doctors have no idea of the future risks they face.

“Doctors are not necessarily being taught,” Cummings notes. “They are learning about oncology, but the concentration is on finding a cure, not on what happens after the cure. The information is often available, but held in the clinical sphere and not getting out to the general medical community.”

When Gloria Gene Moore was diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer 23 years after Hodgkin lymphoma, her oncologist told her “it had absolutely nothing to do with my Hodgkin disease.” Twelve years later, she dealt with angiosarcoma, a rare cancer.

“Through the Facebook groups I realized all of my cancers had been brought on by earlier treatment. And without the Hodgkin’s International screening guidelines Erin developed, I wouldn’t have known to go for heart screenings,” she says. “They discovered that I had an artery that was 100% blocked.”

Part of the mission of Hodgkin’s International is to get this information out not only to survivors, but also to physicians. The group’s website offers care plan documents for survivors and links to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guide specifically for doctors. Cummings hopes those resources will be used not only by Hodgkin survivors, but also by any cancer survivor. “I want to remind people: Don’t be afraid to talk about your cancer,” she says. “Make sure you understand you can be part of the decision-making process.”

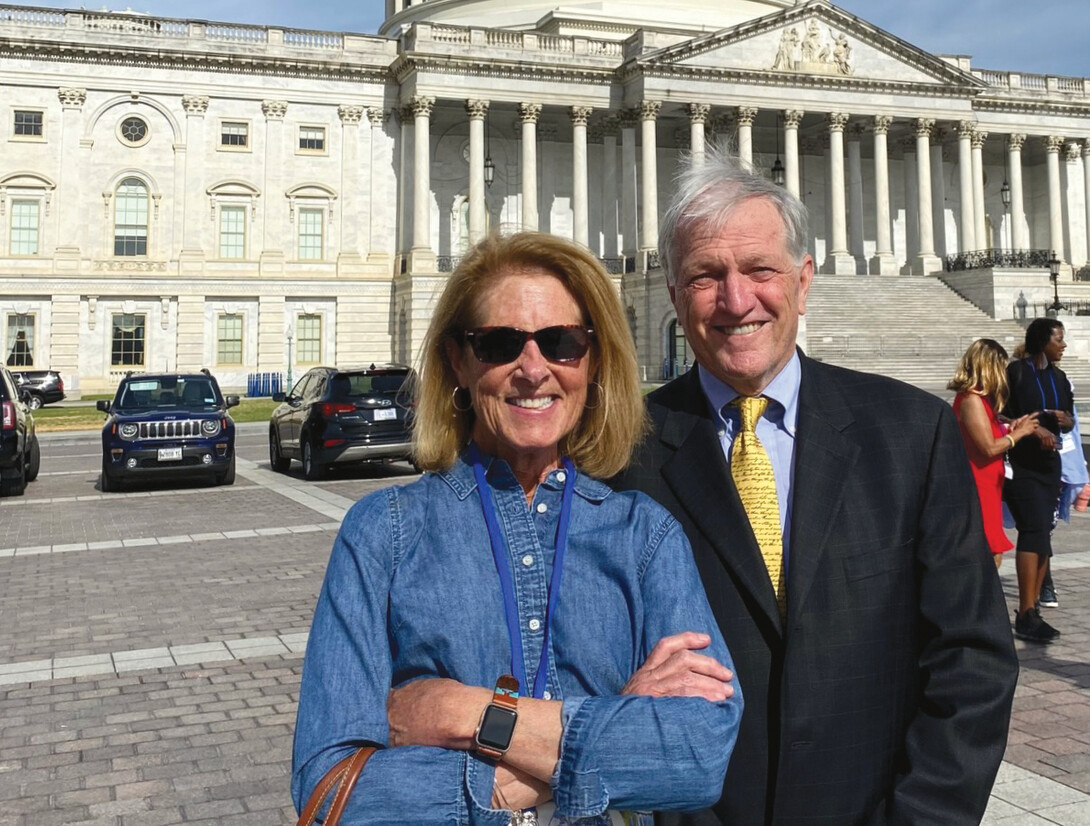

The organization continues to share information through its website, the Facebook group, a monthly newsletter and Zoom meetings, which are later available on YouTube. Cummings also attends the yearly meeting sponsored by the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship and spends time with other survivors on Capitol Hill, advocating for bills that impact cancer survivors.

A Long-Planned Gathering

Hodgkin’s International co-founder Griffin passed away not long after she and Cummings launched the nonprofit. It was another blow, but one that inspired Cummings to host that big party they originally envisioned. Postponed by COVID-19, the first Hodgkin’s International Symposium was held over a June 2024 weekend in Boston. Survivors traveled from across the United States and three European countries for the opportunity to meet Facebook friends and confidants in real life.

“For Erin to get the quality of speakers that she did for our very first Hodgkin symposium was absolutely amazing,” says Susan Leigh, a Hodgkin survivor and a retired oncology nurse. “She successfully procured respected researchers and clinicians from both the National Cancer Institute and other major academic centers, all having a major focus on survivorship education and care. And, more importantly, Erin made sure that survivors themselves were equally represented along with the medical experts during panel discussions.”

“Long-term survivor care is not something that’s in every textbook or in the media,” says Kiran Manisubbu, a second-year medical student at St. George’s University in Grenada, who found information about the symposium online and drove seven hours to attend. “There are probably papers published on it, but information doesn’t find its way to the patient. The conference was so patient-focused, patient-centric.”