By Frank Vellaccio

When Fr. Savard asked if I would be willing to give a short reflection on my experience of having known and worked with and for Fr. Brooks for 38 years, I immediately imagined Father looking down from heaven and thinking, “I should have left clearer and more detailed instructions.” Despite this, I quickly agreed because Father’s passing has left me with such intense feelings of loss and emptiness that I yearned for an opportunity to begin the process of replacing them with renewed hope and vigor. I also knew that Father would want at his wake some laughter mixed with all the tears.

My earliest memory of Fr. Brooks was at the President's reception in September of 1974 when I first started at the College. I was determined to meet my boss even though I had heard that he did not suffer fools gladly. Each time I eyed this dark-haired, stately man, he was surrounded by people. Feeling increasingly intimidated and finding solace in the shrimp bowl, I kept looking for my opportunity to introduce myself. The clock ticked on and the crowd thinned out and still the time didn't seem right. For a brief moment, I turned to talk to a fellow shrimp eater, and by the time I turned back it appeared that Father had made a quick escape. Totally disgusted by my failure to meet him I left Hogan just as it began to pour. As I walked down the road with my head down in the rain without an umbrella, a large car slowed, and, as it was passing—a window lowered and a voice said—“It’s raining, do you want a ride?” Depressed I just grunted, “No, thank you,” without looking. As the car went past I glanced up in time to see the back of Father’s head. In the end he had given me the opportunity I had been waiting for and I botched it. I went home and told Cathy not to get too settled in for we wouldn’t be in Worcester for very long. I remembered this story the day Father asked me to be the first lay Dean of the College, and I thought, “I am not turning down the offer of a ride from him a second time.”

Another early memory of Father was when I was on the Educational Policy Committee—the EPC—which at that time was the College’s most important committee. Being new to the academic political scene, I was unaware of the fact that, due to Father's somewhat authoritative style, many lay faculty yearned for a governance structure where the President had a less prominent role. I remember a meeting at which a faculty member was making a noble attempt at explaining to Father that the EPC discussions were often cursory and abbreviated because Father's style and lack of patience often intimidated faculty, and as a result they were reluctant to express their opinion. Father's face became somewhat reddened (a condition that often overcame him), and he slammed his fist on the table and yelled, “That is the most ridiculous thing I ever heard!” At which point the discussion abruptly ended and we went on to another topic. I thought at that moment this was a man I would follow into battle. And there were many battles we fought together and none we lost.

Father and I traveled quite a bit when I was Dean, including to Australia. During our 14-hour flight from Los Angeles to Sydney, halfway over the Pacific with nothing but the vast ocean under us—the oxygen masks dropped from their compartments and immediately a voice came over the intercom saying, “This is a real emergency, the cabin is rapidly becoming de-pressurized.” Convinced there was absolutely no air left on the plane, I desperately lunged for the mask, sucking into it for everything I was worth. Hyperventilating and intoxicated from my new oxygen-rich atmosphere, I began to accept the inevitability of one of four fates—death on impact, death from drowning, death by sharks, or perhaps worse of all, being stranded on a life raft with Fr. Brooks and after several weeks probably being eaten by him. This thought jarred my consciousness and suddenly I remembered to check to see if I could help Father. There he was sitting next to me calmly sipping his scotch and reading a magazine, totally ignoring the yellow mask hanging before him. Unable to be inspired by his example, I screamed through my mask, “Father, we are going to die!” He slowly turned and in his priestly fashion said, “Frank, relax. You might be worried that in the end we are headed down, but I am confident we are both staying up here.” At that moment I thought, as my life flashed before my eyes, how lucky I was to be working for this great man of immense faith.

There is of course the myth, and then the man. Let me try to set it straight. There are only two things that Father would have left Holy Cross for—to be Commissioner of baseball and Sophia Loren. He was an intensely competitive man and truly hated seeing Holy Cross lose any athletic contest, no matter how big or small. In fact, he was unwilling to accept mediocrity at any level in any area, in any shape or form for any reason. He loved to laugh, to read, to eat and—most important—to be in control. He never lost an argument with anyone he liked, and he never admitted making a mistake because he never remembered making one.

It is ironic that after many years of working for Father, I am now so involved in strategic planning and the elaborate process it involves—since Father didn’t consider strategic planning, if he considered it at all, a group exercise. In fact, he considered process to be the cleaning up others did after he made a decision. I was talking to Father once about his style of leadership and I said that he ruled by benevolent dictatorship. He only questioned the word ‘benevolent.’

By romanticizing about Father’s leadership, I in no way intend to demean how we go about things today. Back then was another time and place. It was Brooks’ time and Brooks’ place, and he never wasted a moment of that time fashioning this place into the finest undergraduate college in the country—bar none.

How did he do it? He was first and foremost a true leader because he was himself a devoted follower—a follower of Jesus Christ. His knowledge of, devotion to, and absolute love for Jesus was the product of a total fusion of his mind and heart. He was a truly brilliant man who used his keen intellect to probe, analyze and discern the mystery that is Christ. But his discernment was energized and fueled by the true and unconditional love he had for Jesus in his heart, and it was this synergy that made him both the fervent follower and the charismatic leader—for he saw the possibility of fulfilling his discipleship to Christ through his leadership of the College of the Holy Cross. And I believe it was this connection that made him love the Cross so passionately and profoundly, right up to his very last minute on this earth. Failure to Fr. Brooks was not a conceivable option, for to fail the Cross was to fail Christ. And for him failure lived in laziness, indecision, in hopelessness, insecurity and weakness, and he would have no part of any of these. He inspired all of us to strive for excellence in all we did because he asked no more from us than he demanded of himself, and he was relentless and unfailing in that pursuit.

I will miss him more than I can explain and more than I think I realize. But I have no doubt that the emptiness I feel now will be filled with hope and renewed vigor, for Fr. Brooks has left us with a lifetime of lessons and a path to follow. As long as we follow that path armed with those lessons, we will bring the Cross to heights that are beyond perhaps what even Father imagined.

Frank Vellaccio is the senior vice president of Holy Cross.

Related Information:

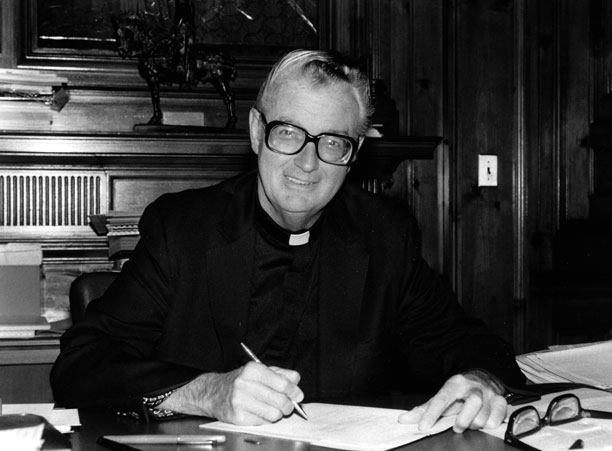

- Photo Gallery: Former Holy Cross President Rev. John E. Brooks, S.J. '49, Laid to Rest

- In Memoriam: Rev. John E. Brooks, S.J. '49, 1923-2012

- NBC’s "Today" Show Features Holy Cross and "Fraternity"