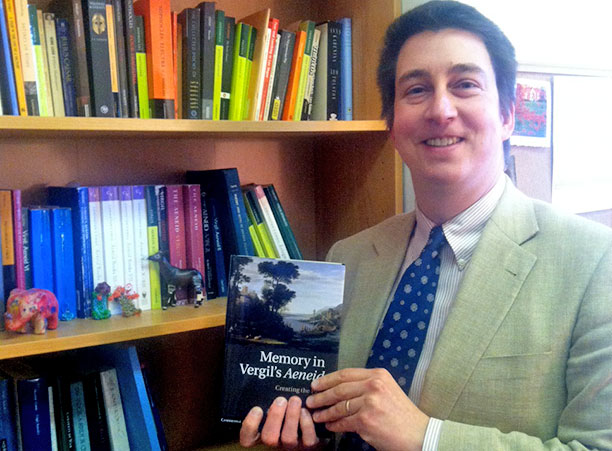

Aaron Seider, assistant professor of classics, recently published his first book, “Memory in Vergil’s Aeneid: Creating the Past” (Cambridge University Press). The achievement marks the culmination of an interest for Seider that began while he was still an undergraduate student.

Seider, a member of the classics department since 2010, confesses that he intended to be an English major at his alma mater of Brown University, but took a Latin class his freshman year and fell in love with both the language and Ancient Roman culture. He studied abroad in Rome during his junior year, and jokes that he’s enjoyed remaining in the classics field for the “opportunity it presents for traveling back [to Italy] as much as possible.”

Seider first encountered his book’s source material as a student in an upper-level class at Brown. Years later, it would serve as the topic of his dissertation while pursuing his doctorate at the University of Chicago. That dissertation now forms the skeleton of this new book. Composed during the height of Rome’s turbulent transition period from republic to empire, Vergil’s epic poem stands among the likes of Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey” in terms of its importance to Western literature.

The plot details the trials and tribulations of the Trojan hero Aeneas and his small band of followers as they escape from the destruction of Troy by the Greeks and attempt to establish a new way of life for themselves and their heritage. There are dark tones of loss and guilt in almost every one of the Aeneid’s 12 books; Aeneas and the refugees encounter loss and struggle at every stage of their years-long journey, with the prior destruction of Troy and the Trojan culture hanging over the group like shade for the entire duration.

Seider observes that Aeneas has an early kind of what modern readers would recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder after escaping the destruction of his homeland, and has, “the original survivor’s guilt.” As a warrior of the times, he would have been expected to die along with the rest of his country. Instead, he escaped death and went on to endure, his former life reduced to a pile of ashes behind him. As a focus in the book, Seider asks: How should Aeneas and the remaining Trojans remember the past? How do they move forward from their catastrophe?

“Memories are not Kodak moments,” but are instead, “created from and influenced by current surroundings and circumstances” Seider says. It’s a major victory, then, when the Trojans can turn their nostalgia into an ideal for the new settlement in Italy, founding a civilization that would eventually evolve over the centuries into the superpower that was the Roman Empire.

The timeline for Seider’s achievement was fortunately much shorter. He first contacted his publisher in the summer of 2011, and the book reached shelves in October 2013.

In addition to his students who keep him “actively engaged in the subject material on a day-to-day basis,” Seider says he is deeply grateful to classics department chair Mary Ebbott and Thomas Martin, Jeremiah W. O'Connor Professor of Classics, and his other department colleagues for their acceptance and encouragement in the project.

Related Information: