Deep in the stacks of Dinand Library, Jane McGrail ’17 knelt on the floor, surrounded by a wealth of information contained by the library’s half-million volumes.

Deep in the stacks of Dinand Library, Jane McGrail ’17 knelt on the floor, surrounded by a wealth of information contained by the library’s half-million volumes.

But that afternoon, she was on the hunt for a different kind of treasure. She thumbed carefully through the yellowed pages of a book titled “The Life of Charles Dickens,” written by John Forster and printed in the late 1800s.

“Here’s an interesting inscription!” she said excitedly, stopping to point to a handwritten scrawl in black ink.

Those traces of the pen, some say, are just as valuable as the printed words inside. It’s evidence of the human hands that touched the book, turned its pages and perhaps gifted that particular copy to a friend or loved one.

And as more people consume information in digital formats, some worry those pieces of human history — and the insight they can offer about the people who left them behind — are atrisk of being lost forever.

“These are cultural treasures,” says Jonathan Mulrooney, associate professor and chair of the English department. “Within these books are personal, written responses to (the words). There are flowers pressed into the pages. Something in the text prompted a particular feeling by the readers. And when you put these findings together, cultural histories can emerge.”

The Book Traces Project

To unearth the treasures hidden between the pages at Dinand Library, Mulrooney partnered with Andrew Stauffer, associate professor of English at the University of Virginia (UVA), and organized a scavenger hunt in the spring that sent students and faculty scouring the library for books augmented by readers of the past. Stauffer has held several similar events at colleges and universities across the country as part of Book Traces, the project he founded in 2014 to inspire others to join the search and start a national conversation about the value hardcopy books hold.

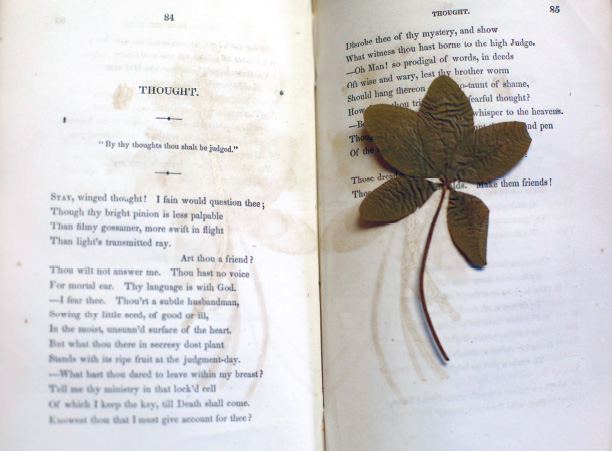

“What makes them valuable are the traces of history inside,” Stauffer said, standing in Dinand’s browsing room, leaning over a selection of old texts students had already culled from the shelves. Inside one book, a newspaper clipping had been glued to the cover. Another held a pressed Akebia quinata leaf. One reader had taken the time to draft an entire poem.

A pressed Akebia quinata leaf, discovered in a book in Dinand Library by Andrew Stauffer, founder of the Book Traces project, during a Book Traces event on campus. Photo by Tom Rettig

A pressed Akebia quinata leaf, discovered in a book in Dinand Library by Andrew Stauffer, founder of the Book Traces project, during a Book Traces event on campus. Photo by Tom RettigWhat Readers Leave Behind

Dinand Library was built and dedicated in 1927 as part of a post-World War I campus expansion, and renovated in 1979 to include the Hiatt wings. By and large, the books it holds were private collections donated to the College. One of the things that make Dinand’s acquisitions unique, Mulrooney says, is its significant collection of late 19th and early 20th century Irish-American literature.

That was a period of time when “books were king and almost everyone could read,” says Stauffer. They were the primary source of entertainment, comparable to today’s social media. When someone wanted to give a gift, the top choice was usually a book, complete with a personalized note scrawled inside.

Scavenger hunts held in connection with Book Traces across the country have turned up many augmentations made by women, Mulrooney says. One such discovery was contained in multiple copies of a poetry book owned by UVA. At least three of them had notes in the margins, written by women, about children they had lost.

“Something in those poems prompted a particular feeling to which people were responding,” he says. “That can tell us something about the way women were dealing with losing children in that time period. And every single library around the country has these kinds of stories to tell that can be connected.”

The Book Traces project came to Holy Cross on April 6-7, 2017, and students combed the stacks in Dinand Library for what readers left behind in books. Photo by Tom Rettig

The Book Traces project came to Holy Cross on April 6-7, 2017, and students combed the stacks in Dinand Library for what readers left behind in books. Photo by Tom RettigThat’s the same reason many college and university libraries are questioning whether storing these books — oftentimes several copies of the same book — is the best use of their limited space. Many higher education communities are mulling the idea of modernizing traditional library spaces to include “collision zones” and Internet hubs, where groups of students can collaborate and exchange information for research projects and study groups.

The Future at Dinand Library

Holy Cross has found itself pondering similar questions. In fall 2013, the College assembled a committee, dubbed Dinand 2020, to research and assess library trends in higher education. The committee was charged with envisioning a future Dinand that would serve as an “intellectual hub of the College,” according to the committee’s final report, produced in May 2014. That report proposed a number of changes, including: physical renovations; greater variety of study and social spaces to allow for silent and collaborative learning; better incorporation of and access to technology; and new programming.

To accommodate those evolutions, and in sync with the “natural shift in the face of electronic publishing,” the report proposed that the College develop a plan to slowly reduce the library’s overall holdings by 15 to 20 percent. The plan, developed in consultation with an outside agency, moved too aggressively and was protested loudly by a number of faculty. The College agreed more discussion was needed and appointed a second committee to carefully assess the collections and recommend next steps.

The task of implementing those recommendations landed in the hands of Mark Shelton, who joined Holy Cross as director of library services in July 2016. He has dedicated much of the last year to meeting with academic departments to discuss the issue. As a collections librarian — which, by definition, focuses on identifying content and building collections — he says he understands the issues libraries face today.

“Our challenge is to maintain the library as a living, organic entity that needs to breathe and change and adjust, while also continuing to grow,” he says. “Information today comes in so many different forms. You have to respect the positives and negatives of each different format, so you can maximize the kinds of information that people have access to. We’re here to facilitate people’s access, not get in the way of it.”

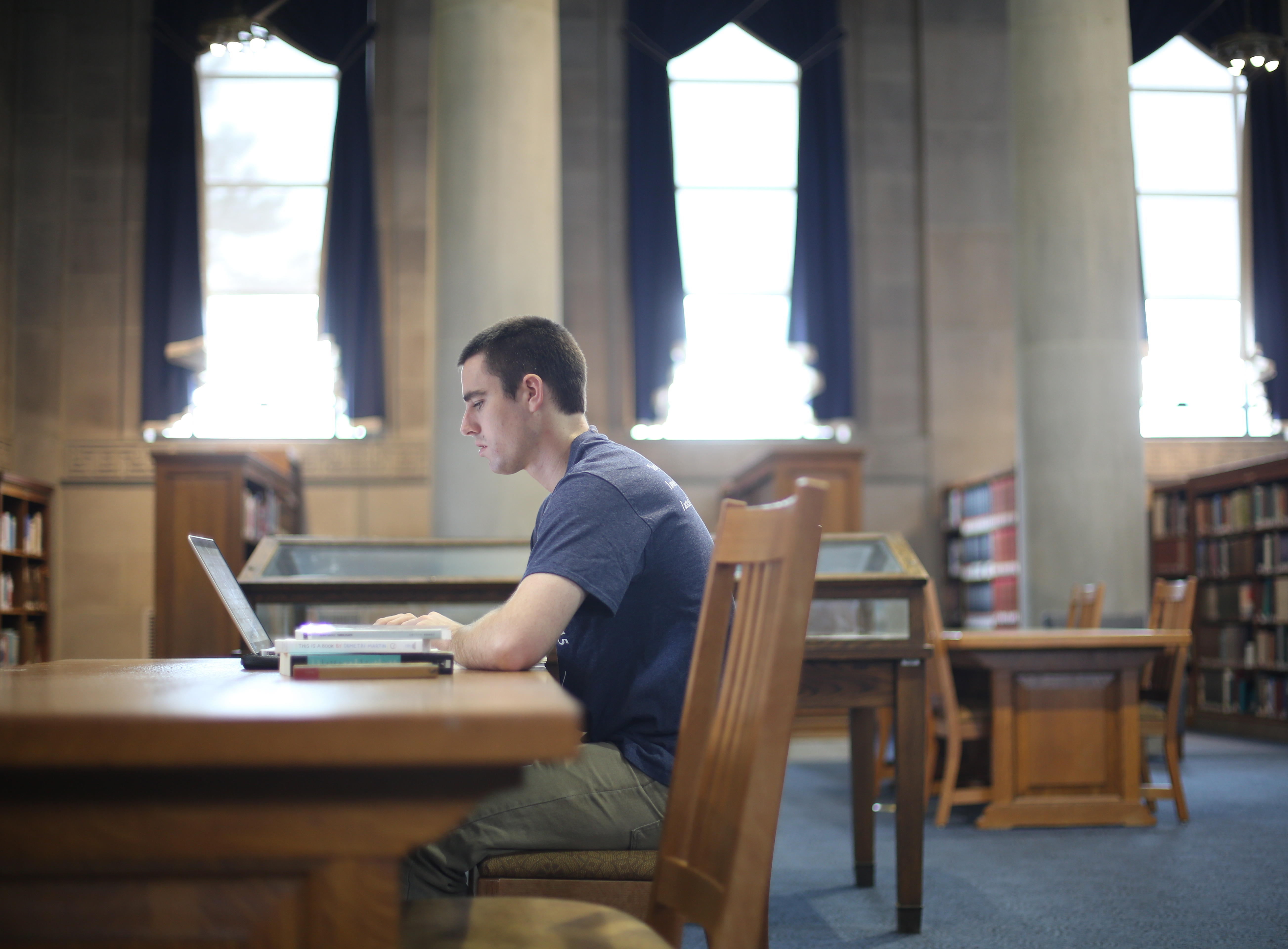

A student at work in the main reading room of Dinand Library. Photo by Tom Rettig

A student at work in the main reading room of Dinand Library. Photo by Tom Rettig“E-books are good for things like edited works, where a single chapter is what you want,” Shelton says. “A journal is a whole bunch of smaller, digestible units. Most faculty and staff go online and download a PDF, so we’re starting to look at these journals as a way to create a little more flexibility.”

He is also working to expand the boundaries of Dinand’s content by purchasing e-books that don’t take up additional space on the shelves, while thinking about how the library’s physical space could be used more efficiently. Hosting the Book Traces project, and reflecting on the value of the printed word, is a valuable part of the process, he says.

“I think the value of a library is not just in the books themselves, but on each individual page,” he says. “A book allows you to stop, pause, handle, smell and feel the weight of the information inside. And to feel the weight of that diversity of thought; to move, browse and discover something new — the library is that place. It allows you to put different books side by side on different issues, so you can process them and figure out how you see the world.”

The Value of the Printed Word

For Associate Professor of English Deb Gettelman, who participated in the Book Traces scavenger hunt, this kind of research is important for the Holy Cross community.

“It’s about preserving Holy Cross’ history,” she says. “I’m fascinated by the idea of how this collection developed, and who gave these books.”

For others, particularly students, it can be a deeper and more personal introduction to the stacks.

“It’s an interesting way to get to know the library,” says Zach Williams ’17, a music major, who flipped through a blue book on the English Romantic Movement, published in 1893. “It’s really cool to see what people thought while reading.”

Stauffer says he created Book Traces not so much to preserve every scrawl and doodle, but rather to spark important conversation about what the digital age means for this trove of tangible treasures. When scavengers discover something worth sharing, they snap a photo of it with their smartphone, and — ironically enough — upload it to Booktraces.org. More than 700 books have been archived in this manner since he started the project.

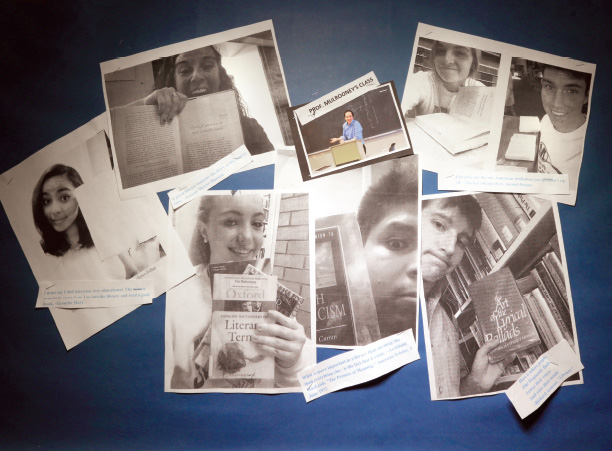

English Professor Jonathan Mulrooney asks his students to take a “selfie” as proof that they went to the library and consulted a print source, and then he displays the selfies on the bulletin board in the hallway of the English department. Photo by Tom Rettig

English Professor Jonathan Mulrooney asks his students to take a “selfie” as proof that they went to the library and consulted a print source, and then he displays the selfies on the bulletin board in the hallway of the English department. Photo by Tom RettigMulrooney, for one, is doing his part to get his students off their tablets and into the stacks. When assigning a project, he says, he often includes a rather unusual instruction along with the typical research.

“I say to my students, ‘Go to the library, find a book — and take a selfie with it, so I know you held the book in your hand.’”

Written by Rebecca Fater for the Summer 2017 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.