Weiss Summer Research Program: 71 students in the natural sciences; 30 in the humanities, social sciences, and fine arts; and six in economics.

The far-ranging research projects gave students the opportunity to dive into topics that intrigue them through intensive, focused projects conducted under the guidance of faculty members who acted as both advisors and research partners. Research took place in labs and libraries on campus, as well within the local community and across New England.

Check out some of the research projects students explored:

.temp123 {

clear:both;

margin: 0 auto;

margin-left: auto;

margin-right: auto;

text-align:center;

}

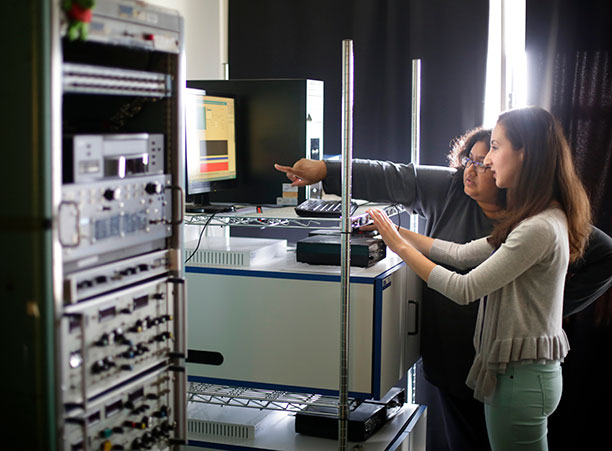

Light & Lasers

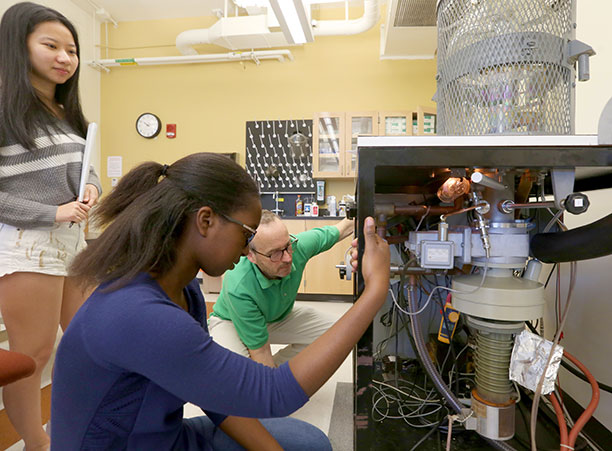

Yihui Jin ’19, Chantal Umuhoza ’20, and Timothy Roach, associate professor of physics, prepare the vacuum thermal evaporation system to coat laser chips with the hopes of reduce the chips’ reflectivity and therefore improving the laser’s accuracy.

Yihui Jin ’19, Chantal Umuhoza ’20, and Timothy Roach, associate professor of physics, prepare the vacuum thermal evaporation system to coat laser chips with the hopes of reduce the chips’ reflectivity and therefore improving the laser’s accuracy.Student Researcher: Chantal Umuhoza ’20, physics major; and Yihui Jin ’19, physics and mathematics double major

Faculty Advisor: Timothy Roach, associate professor of physics

The Research: How do you make a laser more precise? Roach, Umuhoza and Jin tackled this question by focusing in on a semiconductor laser “chip” found inside their custom-built laser system. The chip amplifies light inside the laser system, which then emits a beam of light with extremely precise yet adjustable wavelength — what you’d want in a laser. However, the reflection of light from the front of the chip can cause instabilities in the system — what you definitely don’t want in a laser.

Drawing on established methods of vacuum evaporation to create their own coating process, the research team covered one side of the chip with a thin layer of silicon monoxide in order to reduce the reflectivity, and then studied how the stability of the laser system was affected by the change.

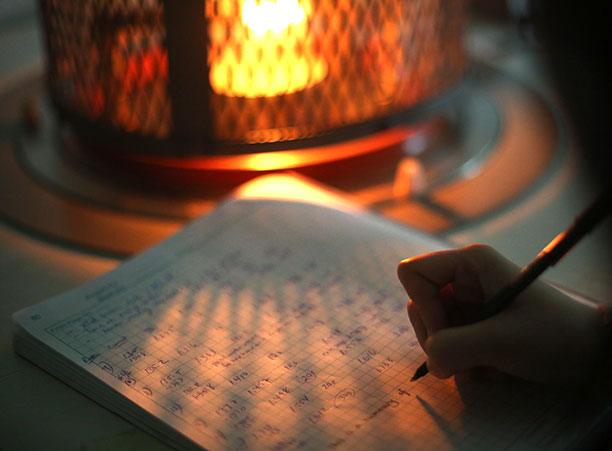

Yihui Jin ’19 notes any changes in the chips’ reflectivity before, during, and after the coating process next to the glowing vacuum thermal evaporation system.

Yihui Jin ’19 notes any changes in the chips’ reflectivity before, during, and after the coating process next to the glowing vacuum thermal evaporation system.“The fact that a problem occurs, is solved, then new ones arise is the fun part that motivates me to keep exploring and stay excited throughout the research,” says Jin, who along with Umuhoza, was eager to spend her summer directly applying her knowledge outside of the classroom.

By doing summer research, I was able to work closely with my professor as a scientist.

By doing summer research, I was able to work closely with my professor as a scientist.— Yihui Jin ’19

“By doing summer research, I was able to work closely with my professor as a scientist,” she shares. Along the way, Jin also discovered her interest in data analysis, this project perfectly marrying her physics and mathematics majors.

For Umuhoza, an international student from Rwanda who decided to tackle research after just finishing her first year at Holy Cross, Roach’s accessibility and mentorship was particularly important.

“Professor Roach’s insights on the projects were really interesting, and I learned to think outside the box,” she says. “He listened very well to my thoughts and considered them, which is something I was really grateful for.”

Both students are looking forward to taking their knowledge and experience with them next year — Umuhoza to her classes on campus, and Jin to her tutorials at Oxford University while studying abroad in England.

“Whether they go into engineering, scientific research, law, or medicine,” says Roach, “this is an almost unmatched opportunity to find out what they are good at and what they like doing and to gain 'integrative' practical skills.”

Queering the Archive

(from left) Carly Priest ’18, Stephanie Yuhl, professor of history, and Emily Breakell ’17 examine transgender-related historical material they identified at the American Antiquarian Society.

(from left) Carly Priest ’18, Stephanie Yuhl, professor of history, and Emily Breakell ’17 examine transgender-related historical material they identified at the American Antiquarian Society.Student Researcher: Carly Priest ’18, history and English double major; and Emily Breakell ’17, political science major with concentrations in Latin American and Latino studies, and peace and conflict studies

Faculty Advisor: Stephanie Yuhl, professor of history

The Research: Like other historians and scholars who visit the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) in Worcester, Priest and Breakell carefully studied the national research library’s renowned collections — but in a way that few have before.

The research pair spent the summer working their way through the AAS’s renowned collection of primary sources, printed in the United States pre-1876, to identify transgender-related historical material. By “queering the archive,” Priest and Breakell reimagined the potential meaning of known historical sources and their relevancy to scholars of gender and sexuality. In addition to identifying these documents, which predate most materials in even the most notable trans archives, they created a finding aid for the AAS to make the material even more accessible for future researchers.

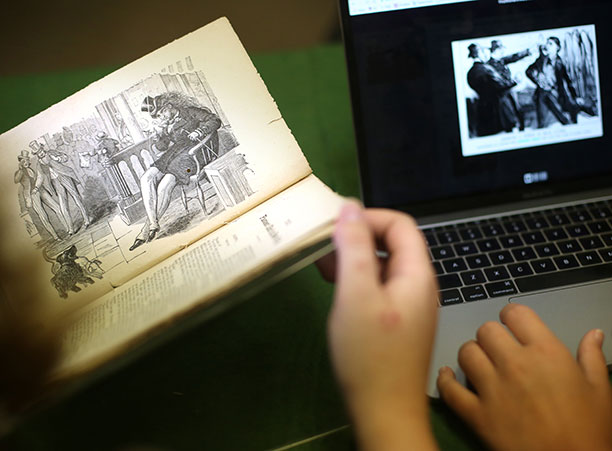

Detail of two examples of transgender-related historical materials Priest and Breakell identified at the American Antiquarian Society.

Detail of two examples of transgender-related historical materials Priest and Breakell identified at the American Antiquarian Society.While the discoveries of transgender-related materials at the AAS were numerous, the process for discovering them was slow, meticulous, and disciplined.

“Their work has required keen attention to language, context, and audience, but also deep respect and humility before questions of the past,” says Yuhl. “Perhaps most importantly, Emily and Carly have successfully resisted the natural impulse to read backwards onto these sources, to see them only through the lens of present-day political values. That is the job of the historian and it is no easy feat, especially with source material of this nature.”

Priest and Breakell also worked with the Digital Transgender Archive (DTA), an online collection of transgender-related historical materials, directed by K.J. Rawson, assistant professor of English at Holy Cross. Similar to the DTA, with which they will share their finding aid, this project’s mission is to uncover and make accessible transgender history and materials.

Because without sources, Yuhl explains, richer and more complex histories cannot be told.

“This research complicates our national narrative on citizenship, sexuality, and power by revealing a long history of trans practice and persons in the United States and by pushing back against false and highly politicized assumptions that transgender personhood is somehow a modern conceit,” Yuhl adds.

“While identifying these sources in the American Antiquarian Society shows the transgender experience is a human experience,” Priest explains, “it also reveals transgender history was, and remains, American history.”

In wrapping up the research at the close of the summer, Priest, Breakell, and Yuhl note that there is plenty of work left to be done and are hopeful that the research will continue with future summer research teams.

Exploring Sounds for a Silent Film

(from left) Chris Arrell, associate professor of music, and Zhiran Xu ’19 explore ways to build software and create sounds to compliment Charlie Chaplain’s silent film “The Immigrant.”

(from left) Chris Arrell, associate professor of music, and Zhiran Xu ’19 explore ways to build software and create sounds to compliment Charlie Chaplain’s silent film “The Immigrant.”Student Researcher: Zhiran Xu ’19, music and computer science double major

Faculty Advisor: Chris Arrell, associate professor of music

The Research: Imagine having nine weeks to create a film score made up entirely of original sounds. The goal, while ambitious, did not intimidate Xu, who spent her summer coding music for Charlie Chaplin’s silent comedy short “The Immigrant.” That means that as she was imagining the score to the 24-minute film, Xu was simultaneously building the computer software to create the sounds within the score. Because of the endless opportunities available with digital synthesis, Xu’s score was not comprised of imitations of acoustic instruments, but rather was a creative exploration of the possibilities of sound.

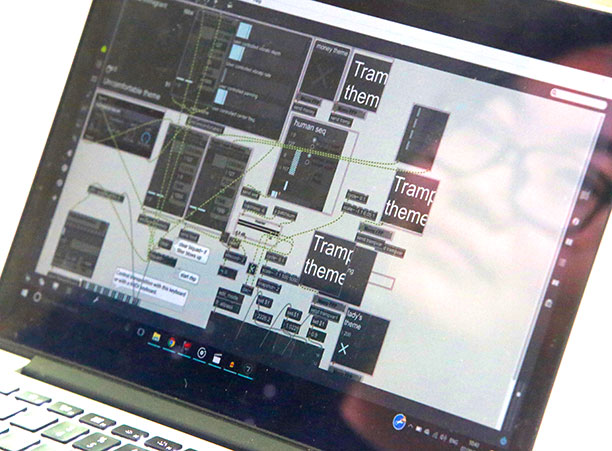

Xu builds matrix of sounds using computer software to compose a score for the silent film.

Xu builds matrix of sounds using computer software to compose a score for the silent film.Xu decided to take what she’d learned in Arrell’s class and run with it this summer, choosing “The Immigrant” as center of her next venture. Considering today’s heated debate on immigration issues, Xu saw this project as an opportunity to contribute her voice to the debate.

She began by breaking the film into pieces and identifying major themes before composing music with characteristics that corresponded to each theme. The process was not as easy as it sounds.

“What kind of color do I want the sound to have? How do I arrange and transition between materials so that they make an impression on listeners but don’t last long enough for them to get bored?” Xu asked herself.

The independent research experience has definitely encouraged me to have wilder ideas because some of my wildest ideas turned out to be my best ideas.

The independent research experience has definitely encouraged me to have wilder ideas because some of my wildest ideas turned out to be my best ideas.— Zhiran Xu ’19

“There are so many possibilities for me to explore and to play around with that makes this process fun,” says Xu. “The independent research experience has definitely encouraged me to have wilder ideas because some of my wildest ideas turned out to be my best ideas.”

Xu worked on-on-one with Arrell to troubleshoot through sticking points and explored more advanced techniques with his guidance, like the use of generative musical systems. Through this technique, she addressed certain themes by creating random sounds within the frequencies she has chosen and on the same scale, ensuring certain musical qualities while also involving an element of chance.

“The intense, focused study afforded by this sort of research offers undergraduates the rare opportunity to pursue extended projects in a context that closely parallels graduate-level study,” says Arrell.

Green Building, Architecture & Holy Cross

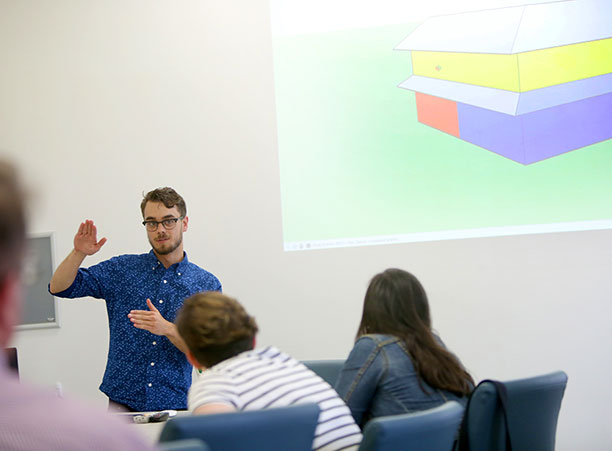

Joseph Metrano ’18 presents his architectural renderings for critique midway through the summer.

Joseph Metrano ’18 presents his architectural renderings for critique midway through the summer.Student Researcher: Joseph Metrano ’18, self-designed architecture studies and studio art double major

Faculty Advisor: Rachelle Beaudoin, visual arts lecturer

The Research: A staunch environmentalist studying art and architecture, Metrano spent the summer exploring sustainable housing — and how that might look at Holy Cross. “While 'green building' has become good practice in the architectural field, little has been done to create buildings that physically give back to their respective ecosystems,” says Metrano.

This led him to explore Living Future Institute's Living Building Challenge (LBC), the world’s most rigorous green-building standard that encourages architects and builders to erect structures that do just that.

“Coupled with an increasing demand for campus-owned housing at Holy Cross,” Metrano explains, “I felt that designing a theoretical student housing complex per the guidelines of the LBC could provide our College with a new direction — not only in regards to green building, but also in developing a campus-wide mindset of sustainability.”

Metrano describes the different parts of his sustainable housing units during a critique.

Metrano describes the different parts of his sustainable housing units during a critique.In addition to reading through literature about green building and the LBC, Metrano traveled throughout New England to see these practices in action, visiting buildings made from locally sourced and salvaged materials, ones that harvest and re-use resources or are entirely off-the-grid, or have on-site waste treatment systems. Much of his travel time was spent observing the practices of college campuses.

“Joe was able to see first-hand what other schools are doing and this led to adjustments and new directions in his project,” Beaudoin explains.

Metrano’s design inspiration began with the tiny houses movement, with the goal of having a compact space for living that met high sustainability standards. After deciding to design units that could be configured in multiple different combinations on the plot of land cornered by Southbridge and College Streets on the bottom of College Hill, Metrano had to address just about everything else.

How would the elevations of the plot impact the design? Would there be enough light coming into the upstairs of the unit, especially during New England winters? How thick should the walls be?

The project allowed Metrano to flex his creativity and rediscover his passion for building and design. But personal takeaways aside, he hopes his sustainable housing units would benefit the Holy Cross community far beyond of their practical application.

“While a single building (or building complex) would have a marginal impact on the College's carbon footprint,” Metrano explains, “it would facilitate education about green building, encourage the administration to take on more sustainable projects in the future, and ideally create a campus environment in which issues of climate change and climate justice are at the top of students' minds.”

Understanding the Brain

(from left) Alo Basu, associate professor of psychology, and Natalie Auteri ’19 discuss the results Auteri has observed while studying fear responses in mice.

(from left) Alo Basu, associate professor of psychology, and Natalie Auteri ’19 discuss the results Auteri has observed while studying fear responses in mice.Student Researcher: Natalie Auteri ’19, psychology major

Faculty Advisor: Alo Basu, associate professor of psychology

The Research: The brain is complex — and therefore so are the mechanisms involved in emotional learning and memory. This summer, Auteri was specifically interested in exploring the neural processes underlying fear memories.

Using Pavlovian conditioning to condition fear responses in mice, Auteri then worked to pull apart and characterize the responses, which are anything but simple. It’s not always clear, Auteri explains, whether the fear is a result of the conditioning or if the mouse is displaying generalized fear, which is the fear of stimuli other than the stimulus they've been conditioned to fear. Generalized fear may occur in response to general aspects of the laboratory context or the experimenter who handles the mice.

By taking such an analytical approach to understanding the fear responses, says Basu, the project aims to collect information that may be relevant to understanding psychiatric disorders that are characterized by heightened or persistent fear memories and responses, like PTSD.

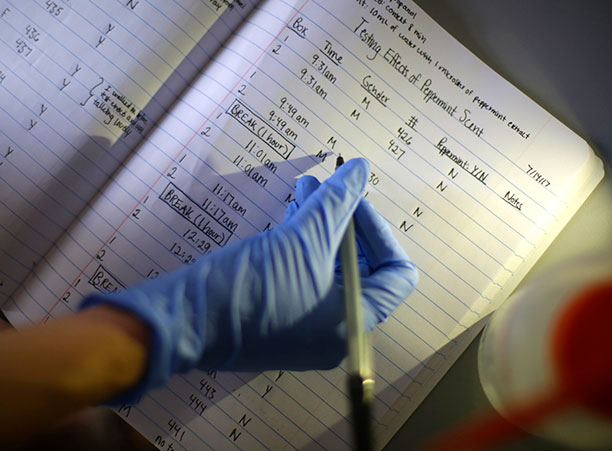

Auteri tracks her observations while testing to identify if the mice’s fear responses are a result of the conditioning or of generalized fear.

Auteri tracks her observations while testing to identify if the mice’s fear responses are a result of the conditioning or of generalized fear.By controlling the systems experimentally, Auteri was able to further probe into fear responses.

“Ultimately what we are able to measure in a mouse is its freezing response, but there could be multiple things that could be making the mouse freeze at the same time,” says Auteri. “So we’re trying to figure out how each of the different components of our setup affect the freezing in the mice.”

Auteri used olfactory cues and spatial inserts to distinguish the context in which the mice were being conditioned, and to observe whether the freezing patterns change as adjustments were made to the context.

The process was one of trial and error, with adjustments being made to the experiment along the way.

“This is novel research; it’s not canned,” says Basu. “We brainstorm and think through ‘Well what questions have we answered, and what questions are still unanswered?’”

Although Basu provided feedback and guidance on the research, she didn’t outline every step, Auteri explains.

“This forced me to become more confident in my ability to make my own choices about how to carry out my research, and made me more comfortable with the unknown,” she says.

Auteri, who plans to declare a neuroscience minor, is eager to the bring the knowledge she has gained back to her psychology and science courses, as well as to find new ways to explore fear learning and memory as she continues this research in the fall.

The student researchers will showcase their work at this year’s 24th Annual Summer Research Symposium on Friday, Sept. 8 from 1–4 p.m. in the Hogan Campus Center Ballroom.

Images by Tom Rettig