Samer Naeem was in his early 20s when he lost his eyesight. He’d been born with a genetic disorder that caused high blood pressure inside the eyeball. One day, while walking the streets of Baghdad, a student hit him in his left eye, causing him to go blind. It wasn’t a random attack. Naeem and his family are Mandaens, a monotheistic religious sect that follows John the Baptist. As a religious minority, the family’s life was difficult in Iraq.

Samer Naeem was in his early 20s when he lost his eyesight. He’d been born with a genetic disorder that caused high blood pressure inside the eyeball. One day, while walking the streets of Baghdad, a student hit him in his left eye, causing him to go blind. It wasn’t a random attack. Naeem and his family are Mandaens, a monotheistic religious sect that follows John the Baptist. As a religious minority, the family’s life was difficult in Iraq.

Eventually they fled to Syria, where, lacking medical attention, Naeem lost his right eye as well, making him now completely blind. Still, he says, “the bombs followed us.” After four years living in fear of the encroaching civil war between the forces of President Bashir Al-Assad and rebel fighters, the family was finally able to apply for a visa to the United States, entering the country in 2013 as part of just 70,000 refugees admitted that year.

Settling in Michigan, Naeem thrived, taking classes in braille and teaching himself English from YouTube videos. “Maybe in September I will go to school to get my GED and I can become a braille teacher,” he says. Nine months ago, he and his family moved to Worcester to be closer to medical specialists in Boston whom he hopes might help restore his eyesight. In a year, he hopes to fulfill his dream of becoming an American citizen. “America saved my life, my family’s life,” Naeem says. “If the United States needs soldiers, even though I can’t see, I will be the first in the military.”

Iraqi refugees from left, Husnivah Thahab, Raghdan Naeem, Ardwan Farhan and Samer Naeem talk with Lou Soiles at their apartment in Worcester. Soiles, a pastor with Worcester Alliance for Refugee Ministry (WARM), helps Samer Naeem with the English language. Photo by Tom Rettig

Iraqi refugees from left, Husnivah Thahab, Raghdan Naeem, Ardwan Farhan and Samer Naeem talk with Lou Soiles at their apartment in Worcester. Soiles, a pastor with Worcester Alliance for Refugee Ministry (WARM), helps Samer Naeem with the English language. Photo by Tom RettigIn addition to talks by refugee experts and presentations of student research, the four-day conference of the Jesuit Universities Humanitarian Action Network (JUHAN) included meetings with refugees at local service agencies. “It’s one thing to hear from experts and practitioners, but it’s very different to provide safe spaces where refugees can actually speak,” says Denis Kennedy, an assistant professor of political science and peace and conflict studies at Holy Cross who helped organize the gathering. “Political discourse right now has been characterized by dehumanization and the imposition of barriers; to provide an opportunity where refugees can engage on a person-to-person, human level is very powerful.”

Denis Kennedy, assistant professor of political science and co-organizer of this year’s JUHAN conference on refugees, in his office. Photo by Tom Rettig

Denis Kennedy, assistant professor of political science and co-organizer of this year’s JUHAN conference on refugees, in his office. Photo by Tom Rettig“There is a very strong conviction biblically that all human beings are members of a common human family, and boundaries between nation states are secondary,” says David Hollenbach, S.J., Pedro Arrupe Distinguished Research Professor at Georgetown School of Foreign Service, who delivered a keynote at the JUHAN conference. He points out that Judaism, Christianity and Islam all have a refugee story at their core — with Moses fleeing from Egypt to Israel; Jesus, Mary and Joseph fleeing from Israel to Egypt; and Mohammed fleeing from Mecca to Medina. “In the final judgement in Matthew, it says that people will be judged by how they respond to the poor and the stranger in their midst,” he continues. “So caring for strangers and migrants is part of the determination of our salvation.”

Accompaniment, Service and Advocacy

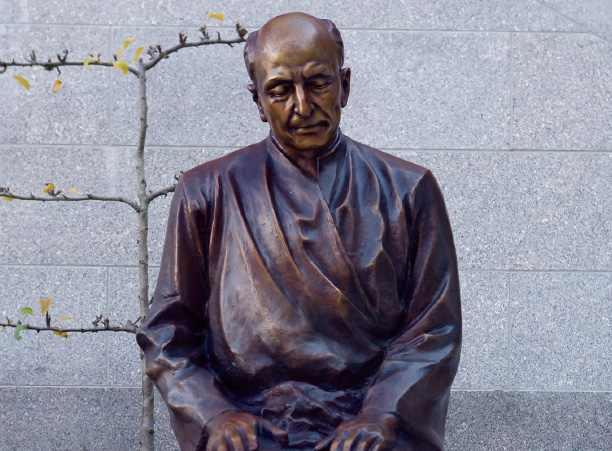

Jesuit leader Rev. Pedro Arrupe, S.J., took that message to heart in the late 1970s when he articulated the mission of Jesuit education as “men and women for others.” At the time, he was moved by the plight of the so-called “boat people,” who were fleeing from Vietnam and Cambodia in the wake of the Vietnam War, often risking their lives on unstable boats. He put out a call in 1979 for Jesuits around the world to come to the aid of refugees, leading to the formation of the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) a year later. “Saint Ignatius called us to go anywhere where we are most needed for the greater glory of God,” he said, referring to the founder of the Jesuit order, in a speech launching the service. “God is calling us through these helpless people.”

A statue of Rev. Pedro Arrupe, S.J., in front of the Integrated Science Complex on campus at Holy Cross. Photo by Tom Rettig

A statue of Rev. Pedro Arrupe, S.J., in front of the Integrated Science Complex on campus at Holy Cross. Photo by Tom RettigJRS organizes its mission into three pillars: accompaniment, service and advocacy. The first is particularly unique to the Jesuit outlook. “It’s really being with refugees not just as a vulnerable population that needs services, but also as people who need someone to listen to their stories and to hear their needs,” says Giulia McPherson, director of advocacy and operations at JRS/USA. In urban areas outside of refugee camps, JRS visits refugees individually at home, and after hearing their most pressing concerns, often refers them to the outside agency that can best help them.

The bulk of JRS’s own services, perhaps unsurprisingly, target education — a prime focus of the Jesuit order throughout its history. “We make the case that education is just as important and lifesaving as food or water,” says McPherson. The average refugee is displaced in a camp for 15 years, which can mean a whole childhood — and children who have been traumatized by violence often have needs that go beyond just learning math and literature.

Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) provides formal educational services for more than 50,000 primary and secondary school students in the refugee camps in eastern Chad. Photo courtesy JRS.

Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) provides formal educational services for more than 50,000 primary and secondary school students in the refugee camps in eastern Chad. Photo courtesy JRS.In Lebanon, where a half-million school-aged Syrian refugee children have overwhelmed the school system, those pupils often have difficulty assimilating into the established school system due to language barriers, bullying and discrimination. JRS has set up language services for children to help them learn the local Arabic dialect, as well as French and English, which are both taught in schools. The programs have led to better attendance for students, as well as less emotional problems for them in class.

In addition to direct services to refugees overseas, JRS works to change policies through its third pillar — advocacy. In the wake of the Trump administration’s “travel ban” on residents from six predominantly Muslim countries, JRS released a strong statement of condemnation, saying that the executive orders “fly in the face of the core American values of welcoming persecuted families and individuals.”

The organization also sponsors speaking tours of Jesuit universities and advocacy days in Washington to support priorities for refugees, including an increase in the number of refugees allowed to resettle in the U.S., and support for the READ Act, a bill that would prioritize U.S. investment in global education programs.

In their advocacy work, JRS partners with other institutions in the Jesuit network such as the Ignatian Solidarity Network, a U.S.-based organization that mobilizes Jesuit institutions to advocate for comprehensive immigration reform.

That includes recognition for economic migrants crossing the border from Mexico or Central America — many of whom are also fleeing violence and repression. “We have leaders right now who want to simplify the issue, but the world is not black and white,” says the group’s executive director Christopher Kerr. “Jesus called us to live in the midst of that complicated world.”

The devastated city streets of Aleppo, Syria, as seen in February 2017. Photo courtesy JRS Syria

The devastated city streets of Aleppo, Syria, as seen in February 2017. Photo courtesy JRS SyriaThroughout the country, Jesuit universities have answered that call. The Center for Faith in Public Life at Fairfield University, for example, has produced a toolkit called Strangers as Neighbors to help Catholics think about how to better welcome immigrants in their midst. According to polling by the Pew Research Center, 62 percent of Catholics disapprove of President Trump’s proposed travel ban, compared to 45 percent of Protestants. Those numbers, however, mask deep divides between white Catholics, who only disapprove of the ban by 50 percent, and Hispanics and other minorities, who oppose it by 81 percent. Pew found similar, though smaller, divides on other immigration issues, including paths to citizenship for immigrants, and President Trump’s proposed wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

In addressing those racial divides, the Fairfield researchers found that starting with a language based on faith, using words like “brother,” “sister” or “pilgrim,” rather than “migrant” or “newcomer,” helped Catholics to greet immigrants with less bitterness, and talk more constructively about issues, rather than creating an “us versus them” competition over jobs and opportunity.

A Welcoming City

Given its history of successive waves of immigration over the past century, Worcester has continued to be a destination for refugees. Last fall, Mayor Joseph Petty stood with members of the city’s Interfaith Coalition at City Hall to affirm the city’s reputation as a welcoming city; in the spring, Petty sent a strongly worded letter to President Trump opposing his travel ban, saying, “Turning our backs on the innocent women, children and families desperate to escape violence is not only callous and wrong, it is deeply un-American.”

When refugees arrive in the city, they are assigned to one of three support service providers — Ascentria Care Alliance, Catholic Charities or Refugee Immigrant Assistance Center (RIAC) — which administer a federal stipend and provide links to school and other government services for the first three months. After that, however, refugees are left largely on their own, or must seek assistance from local nonprofit groups.

“There is a real need for other groups to partner with refugees for the long haul,” says Susan Rodgers, Holy Cross professor emerita of anthropology. Rodgers, who specializes in Southeast Asia, first read an article about the local Burmese community in the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, and has since become one of many people in the Holy Cross community who volunteer their time to assist refugees.

Paw Wah stands with her tutor and Holy Cross professor emerita of anthropology, Susan Rodgers, outside of the Worcester triple-decker where Wah lives. Photo by Tom Rettig

Paw Wah stands with her tutor and Holy Cross professor emerita of anthropology, Susan Rodgers, outside of the Worcester triple-decker where Wah lives. Photo by Tom Rettig“Many of them have seen relatives killed in front of their eyes, or lived for 10 or 20 years in overcrowded refugee camps where they don’t get enough to eat or adequate medical care, then they come to a brand-new country and have to land on their feet and get a job,” Rodgers says. “Yet they are amazingly tough and resilient, like few native-born Americans I’ve ever met. It’s inspirational to hear their stories.”

Among those stories is that of Paw Wah, a 50-year-old refugee from Myanmar whom Rodgers tutors. Wah is a member of the Karen ethnic minority in northern Myanmar where the ongoing conflict between government soldiers and ethnic militias is one of the longest-running civil wars — and has taken its toll on the local populace. “They burned down our whole village,” she says. “They killed the village leader and tortured the schoolteacher.”

Wah recounts her ordeals in a sun-splashed apartment of a triple-decker on Worcester’s South Side, just down the hill from Holy Cross. Burmese art covers the walls and the table is set with steaming bowls of curried beef, fried rice and fresh cucumbers and tomatoes she grows in a garden out front. In the midst of the Myanmar conflict, Wah’s brother, who had Down syndrome, was tortured by the military and died soon after. Wah and her husband, Pu Ta Ku, made the decision to flee, walking more than a day to the Thai border with their infant son and an orphaned child whom they had found naked and dirty on the streets of their village and informally adopted.

At the refugee camp, they lived in a bamboo hut that lacked running water and had only sparse food and medical care. Wah made the best of the situation, working at the hospital doing home visits for new arrivals to the camp. They stayed in the camp for six years, while Wah had two more sons. When they were finally accepted for asylum in the United States, however, her foster son was not allowed to accompany them. “I said he is like my son, I can’t leave him,” she says. The family waited another two years before he was allowed to come with them.

Burmese refugee Paw Wah stands in her garden. She was honored last year by Worcester Magazine as one of five Hometown Heroes. Photo by Tom Rettig

Burmese refugee Paw Wah stands in her garden. She was honored last year by Worcester Magazine as one of five Hometown Heroes. Photo by Tom RettigAnswering the Call

In addition to work by faculty like Rodgers, Holy Cross students have also aided refugees in Worcester in a number of ways. Through the campus group Student Programs in Urban Development (SPUD), several dozen students volunteer with WRAP and another group called African Community Education to tutor newly-arrived refugees after school. As with JRS, the effort is as much about forming relationships as it is about academic mentoring, says Marty Kelly, faculty adviser for the group and a College chaplain. “It allows students to get off campus and break down barriers, and meet people whose experience is very different than their own,” he says.

Other students work with refugees through the College’s Donelan Office of Community-Based Learning, which integrates service into the academic curriculum. For an upper-level Spanish language course, for example, students may choose to tutor a native Spanish speaker through Ascentria, improving their Spanish in the process, at the same time learning about the culture and history of a refugee’s native country. “At the most basic level, it helps them better comprehend what they are learning from their courses,” says Michelle Sterk Barrett, director of the Donelan Office. “But more than that, it causes students to think about their own privileges and social justice on a larger level, and consider the ethical response to the suffering we see in the world.”

The Donelan Office also helps connect many students to volunteer agencies such as Worcester Alliance for Refugee Ministry (WARM), yet another local nonprofit that helps refugees assimilate. Pastor Lou Soiles, an evangelical minister, works with WARM to furnish apartments for incoming refugees, teach refugees English and how to drive, and invite refugees from all cultures to social gatherings. Soiles’ daughter, Jenna Soiles ’17, credits her time at Holy Cross with deepening her own commitment to helping refugees around the world.

“I am not a Catholic, but I learned the idea of being men and women for others, and it increased my desire to do whatever I can to help with the skills God has given me.” After graduation, Soiles traveled to Lebanon to work as a teacher of young children in a refugee camp. “Some of them literally came in without shoes despite the fact it was cold in November,” she says. “Others were dealing with significant trauma from the war. Just to see them there in the classroom was so powerful.” Soiles is now pursuing a master’s in social work at Worcester State University, and hopes to become a teacher of English as a second language for refugees.

Children wait in line after recess to go back into their classrooms in Baalbek, Lebanon. Baalbek has received the highest number of Syrian refugees and hosts 69 percent of all informal settlements in the country. Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) provides computer literacy classes, early childhood education in three educational centers and extracurricular activities for youth at this school. Photo courtesy JRS.

Children wait in line after recess to go back into their classrooms in Baalbek, Lebanon. Baalbek has received the highest number of Syrian refugees and hosts 69 percent of all informal settlements in the country. Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) provides computer literacy classes, early childhood education in three educational centers and extracurricular activities for youth at this school. Photo courtesy JRS.The conference included a lineup of expert speakers — both local and national, Jesuit and non-Jesuit — who presented a sober assessment of the current state of refugees and what is needed from a policy and service perspective to help them. Throughout the event, organizers strived to provide a balance between reality and hope. “You don’t want people leaving the conference thinking it’s absolutely hopeless; at the same, you don’t want people thinking naively that with a Facebook or Twitter post they are going to change things,” says Kennedy, the political science professor who helped organize the conference. “It’s about getting students to stand back and reflect on the possibilities and limits, and provide them with concrete steps they can take going forward.”

Student organizer Mattie Carroll ’19 was inspired to do more to help refugees after working with Ascentria’s Unaccompanied Refugee Minors program as a community-based learning project during her first semester at Holy Cross. Carroll helped solicit JUHAN conference presentation proposals from faculty and students at Holy Cross and other Jesuit institutions, created posters to advertise it and helped assemble the conference agenda. The conference gave her a more realistic understanding of what humanitarian work entails. “It takes a network of people working at all capacities, not solely people out in the field providing in-person assistance,” she says. “Most importantly, help should be ‘given’ or discerned with the perspective and needs of those receiving aid primarily, not just action taken on the basis of what is thought ‘should’ be done.”

Despite the challenges underscored by the conference, many students left energized to address the refugee crisis in whatever way they can. “I feel like it is my responsibility to use my education to help my brothers and sisters worldwide,” says international studies major Clare Orie ’18. “I will not at the end of my life stand before God and say I didn’t use all of my talents.” She hopes to go into the Peace Corps next year in order to help her eventually gain the skills she’ll need to best contribute to refugees in conflict zones. “I want to make sure I have the right training and am qualified to be there first,” she says.

By taking action, students are continuing a longstanding Jesuit tradition of being with displaced people, and carrying it forward into the future. “Holy Cross has really tried to embody and preach this identity of service to Jesuit values,” Orie says. “It’s just an empty label if we are not trying to live out the mission and act on our responsibilities whenever we can.”

Written by Michael Blanding for the Fall 2017 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.