For 113 Holy Cross students, summer has been a time to dive deep into innovative research through the Weiss Summer Research Program. Sixty-eight students conducted research in the natural sciences; 37 in the humanities, social sciences, and fine arts; and eight in economics.

Under the mentorship of faculty, who act as both sounding boards and research partners, students are engaged in focused projects that speak to their academic interests in profound ways. Many projects took place on campus, in labs or classrooms; others took place around New England — and sometimes far beyond.

Take a look at some of the topics students explored:

Can You Dig It?

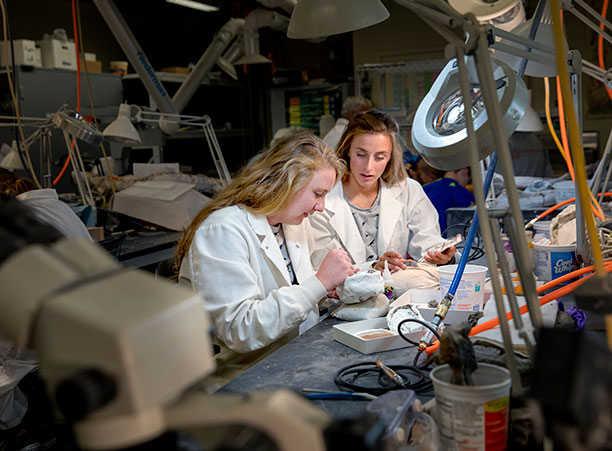

Olivia Lloyd '20 and Leah Zogby '20 inspect fossils at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Photo by Kim Raff

Olivia Lloyd '20 and Leah Zogby '20 inspect fossils at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Photo by Kim Raff"We learned various techniques for excavating extremely delicate, small and often fragmented fossils from the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona," Lloyd says. "One Triassic phytosaur we helped excavate in Wyoming will eventually be in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. There are many species of phytosaurs, and it's possible the one we helped Virginia Tech dig is a new species. It had two main sections; the body jacket and the skull jacket. The skull jacket weighed roughly 1,200 pounds and required a helicopter operation, which we were able to help with."

As a paleontologist, Claessens has taken 15 students over the years to study paleontology in the field, traveling as far as the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

"It is impossible to learn how to find and excavate fossils from a book or in a classroom. You can only learn how to do this out in the field, using your hands and your head, and under the guidance of experienced paleontologists."

While the research seems plucked right out of a Jurassic Park storyline, the students had to adapt to some un-Hollywood-like conditions. Out in the field, they slept in tents with little to no cell phone service or internet access, had few opportunities to shower and constantly battled bugs.

"After getting into the rhythm of the field work, I realized that letting go of being slightly 'uncomfortable' was actually liberating," says Zogby. "The 6:00 a.m. wake ups, many encounters with large insects, extreme heat and weather, and exhausting hikes together created an important learning experience in itself."

Olivia Lloyd '20 and Leah Zogby '20 take a break while digging up fossils in the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. Photo courtesy of Leah Zogby

Olivia Lloyd '20 and Leah Zogby '20 take a break while digging up fossils in the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. Photo courtesy of Leah Zogby"Leah and I have been opening these boxes for the first time since they were packaged in 1980 and sorting through the fossils," says Lloyd. "To prep a fossil, we begin by opening the plaster jackets, made in the field by other paleontologists, with a spin saw. When we open the jackets, the bone is encased in hard or crumbly rock and it is our job to get the bone out as best we can without breaking it. Depending on the type of rock the bone is encased in, we use various tools like dental picks and air scribes to reveal the bone and its fragmented parts. Once the bone is out of the jacket, we spend time cleaning the bone and determining if and where we can glue pieces back together using special formulated acetone consolidant glue."

The hands-on manipulation of fossils may seem far afield from the liberal arts, but Claessens argues just the opposite.

"Paleontology is a highly integrated field, combining knowledge from evolutionary biology, anatomy, ecology, geology and other fields in the pursuit of fundamental questions about the history of life on our planet. Students with a liberal arts background are especially well suited to take a broad, multi-disciplinary approach to these questions."

Though they won't find any fossils when they return to Mount St. James (except in the laboratory), the students plan to continue with research throughout their academic careers. "I hope to study abroad in South Africa, focusing on the social ecological systems and biodiversity throughout various South African national parks," Lloyd says. "The field work experience I've gained this summer has definitely prepared me for this opportunity and provided me with skills that will allow me to make the most out of the trip."

Zogby wants to pursue her newfound passion for paleontological research. "When sitting in a quarry for hours a day, working to dig up the skull of an extinct organism that lived and breathed on this Earth millions of years ago, I couldn't help feel immensely connected to something much larger than the modern world. Seeing how knowledgeable the other scientists were about past life forms motivated me to keep studying the anatomy and evolution of extinct and extant species."

The Art and Artlessness of Pop Poetry

Ryan Fay '20 reads one of the poetry books he's researching for his project on pop poetry with Melissa Schoenberger, assistant professor of English. Photo by Tom Rettig

Ryan Fay '20 reads one of the poetry books he's researching for his project on pop poetry with Melissa Schoenberger, assistant professor of English. Photo by Tom RettigFay's interest in poet populism began with a simple question. "I was interested why so many people were so engaged in it, whereas it seemed self-evidently generic and kitsch to me, and to many others as well. As my research continued, I became more interested how far the implications of pop poetry stretched — from beatnik poetry and jazz to industrial England and German idealism."

The idea of poetry as something public or marketable is not a new one, says Schoenberger. "Eighteenth-century England produced thousands upon thousands of lines of poetry, some of which were produced for the sake of real intellectual engagement, and some of which were pure hackwork written to make a quick buck."

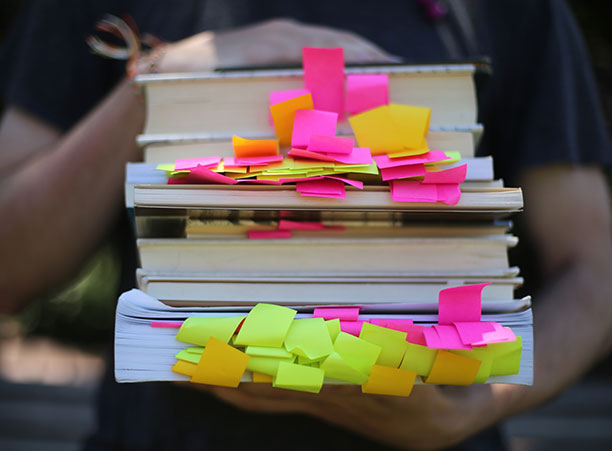

Ryan Fay '20 shows off a stack of books flagged with sticky notes that he's using for his research on pop poetry. Photo by Tom Rettig

Ryan Fay '20 shows off a stack of books flagged with sticky notes that he's using for his research on pop poetry. Photo by Tom RettigFay looked at how poetry is seen as both a high and low art form, examining the implications of formal academia and contemporary capitalism and exploring how we conceptualize art and academia, marginality and class, and gender and consumption.

A few months into his study, Fay is struck by what classic and click-bait poetry share — and don't share. "To be widely consumed, pop poetry must be widely accessible; such poetry, then, is brief, generic and simple enough to be understood in its totality with one quick reading, which is fitting for its mass production and mass consumption. 'Regular' poetry, by contrast, can certainly use generic language and be brief, but it must do so with an acute attention to textual interrelation: the way in which all of the elements of a poem interact, and the ways that these interactions constitute a heightened meaning of language."

When the summer ends, Fay's investigation will continue — this time at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland where he will be studying abroad for the academic year. Then, Fay's thinking about Insta poets might deepen on the streets of Yeats, Wilde and Joyce.

Tiny Technology

Matthew Cummings '20 and Christy Mangiacotti '20 work with a scanning tunneling microscope as L. Gaby Avila-Bront, assistant professor of chemistry, guides them. Photo by Tom Rettig

Matthew Cummings '20 and Christy Mangiacotti '20 work with a scanning tunneling microscope as L. Gaby Avila-Bront, assistant professor of chemistry, guides them. Photo by Tom RettigThe students created and tested sample compound mixtures relevant to nanotechnological applications to better understand how compounds combine together and change when mixed.

"The majority of chemical processes occur on surfaces," explains Avila, "and that creates a surface scientist's dilemma: how is the surface structure and functionality of a compound impacted by its presence in a mixture — such as room temperature and atmospheric conditions — in ambient conditions?"

Prior to tackling any of these scientific questions in the actual lab, Avila had the two students read nearly a dozen papers that explored aspects of her research.

"I wasn't sure if I would be able to contribute a lot to the project because I wasn't confident in what we were actually researching," says Cummings. "Through reading articles and watching Professor Avila run scans, I became confident and excited to contribute to this research. Now, I feel like a valuable member of the lab."

Once Cummings and Mangiacotti had a better grasp of what type of research they'd be conducting, Avila set them up to shadow two students — Caroline Roy '19 and James Gould '20 — who had been working on the project throughout the past academic year.

Matthew Cummings '20 prepares a sample for the scanning tunneling microscope in L. Gaby Avila-Bront's lab. Photo by Tom Rettig

Matthew Cummings '20 prepares a sample for the scanning tunneling microscope in L. Gaby Avila-Bront's lab. Photo by Tom RettigAt first, Cummings was terrified to even go near the microscope. "It was super intimidating that for my first few solo scans, I wasn't getting the same results as my lab mates. Professor Avila and the more experienced students constantly reassured me, and I am now confident in my ability to work the microscope and the software that we use to analyze the images we receive. Having students who have gone through the same uncertainty was very comforting."

It's not a coincidence that Avila's lab is built around a peer-led model. "I set up my lab to encourage these mentor-mentee relationships as much as possible. The older students can solidify their own knowledge, while the younger students get trained by people whose minds and ways of thinking are similar to their own. It's a mutually beneficial relationship that helps the knowledge stick better in both the younger and older students."

By summer's end, the undergrads have grown tremendously. And they can take their new skills forward with them in their studies. "We've learned how to think through experiments and solve problems scientifically," Mangiacotti says. "I can bring this knowledge to any class I take as an undergrad and wherever my post-grad plans might lead."

Asking the Important Questions

Elisaveta Mavrodieva '19 sits with Alvaro Jarrin, assistant professor of anthropology, discussing the interviews she conducted as part of her summer research project on gender inequality in Russia. Photo by Tom Rettig

Elisaveta Mavrodieva '19 sits with Alvaro Jarrin, assistant professor of anthropology, discussing the interviews she conducted as part of her summer research project on gender inequality in Russia. Photo by Tom Rettig"I wanted to see the intergenerational differences between how these women saw themselves and their place in the world during the Soviet Union, during three time periods — World War II, during the perestroika and after the perestroika. I think that looking at history in a linear way limits us to understanding the depth, nuance and complexity of how humans understand culture, meaning and life. So I went and asked questions to those who lived through it, who felt it, and tried to make sense of it all."

While Mavrodieva was born in Volgograd and still has ties there, the decision to interview women from the city on the banks of the Volga River was more than an autobiographical coincidence.

"Volgograd is a hugely historical city because it's where the Battle of Stalingrad took place in World War II, and it was a turnaround point in the war. It was a moment of victory then, but the city was really affected."

And so were the women who lived there. Through the interviews, each of which lasted around two hours, Mavrodieva found, as she anticipated, that each generation viewed the country's progress through their own lens.

"The older generation was discouraged about the shift from social well-being, patriotism and solidarity to a more individualistic focus driven by appearance and materialistic gain. Many spoke of the decrease of safety and stability and reminisced for the past. Everyone has a very nuanced perspective on everything, but generally, the younger generation seems to be experiencing a bit of hopelessness. Some, though, noticed positive changes happening since the 1990s."

Alvaro Jarrin, assistant professor of anthropology, looks over the shoulder of Elisaveta Mavrodieva '19 as they discuss her research. Photo by Tom Rettig

Alvaro Jarrin, assistant professor of anthropology, looks over the shoulder of Elisaveta Mavrodieva '19 as they discuss her research. Photo by Tom Rettig"Russia is a fascinating case because the transition from communism into crony capitalism seems to have exacerbated gender inequality rather than assuaged it. Lisa's interviews with these women reveal how structural conditions in Russia have worsened for everyone, and made life more precarious for young women in particular, who now experience much more limited economic and educational opportunities than previous generations. Given Russia's political influence around the world, it is very important to hear these stories."

Mavrodieva might be back on The Hill, but she suspects she'll be returning to Russia before long. Post-graduation, she hopes pursue a Ph.D. in anthropology. "I am working to build a bridge between personal connections to Russia and my academic life and aspirations, almost in an auto-ethnographic way. It's incredible that anthropology and all of the insight I have gained through my classes allows me to do this."

Data on the Brain

Sarah McGuire '19 talks with David Damiano, professor of mathematics, about the topological data she has collected as part of her research project on behavioral synchrony. Photo by Tom Rettig

Sarah McGuire '19 talks with David Damiano, professor of mathematics, about the topological data she has collected as part of her research project on behavioral synchrony. Photo by Tom RettigMcGuire has been working with the two professors since the fall of 2016 to conduct research on how interpersonal synchrony, or the tendency of people to mimic and fall into rhythm with one another, corresponds to functional networks in the brain — especially in those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

As Schmidt explains, "As it turns out, this interactional synchronization is a bio-behavioral marker for healthy social interaction and breaks down in autism and schizophrenia. Consequently, identifying the brain networks associated with interactional synchrony is of great importance for our future understanding of the impaired mechanisms of these disorders."

McGuire's role in the research is both analytical and hands-on. "We analyze electroencephalograph (EEG) activity from an experiment involving participant pairs swinging pendulums in different coordination conditions. We then use methods of topological data analysis, which involves mapping data points into generalizations of graphs and analyzing their geometric properties to detect global features of the data."

And the findings have been encouraging, says McGuire. "For the past year, we have been working with data from pairs of undergraduate students performing the synchrony tasks. Now, we are starting to apply these methods to data from adolescent and parent pairs — some with ASD and some developing adolescents. Ultimately, we are interested in neurophysiological differences in adolescents with ASD that occur while performing these tasks of interpersonal synchrony."

Sarah McGuire '19 and David Damiano, professor of mathematics, point to individual brain scans plotted out as topographical data. Photo by Tom Rettig

Sarah McGuire '19 and David Damiano, professor of mathematics, point to individual brain scans plotted out as topographical data. Photo by Tom RettigAs an affirmed mathematician, McGuire had to get up to speed on the psychology side of the equation, filling in the gaps by reading academic journals and consulting with Schmidt.

"The exploratory data analysis nature of this project lends itself to work complementary with both disciplines. Approaching a problem with a computational mindset, and from multiple perspectives, allows you to break down the problem into pieces and creatively reorganize, analyze and interpret it."

Schmidt and Damiano had been thinking about working together for a while before starting this project. And when they needed a student to help them with the research, McGuire, who was skilled in topology and had an interest in psychology, was the perfect fit, Damiano says. She's been working on the project ever since, tying it into her upcoming senior thesis and work as a Clare Booth Luce scholar for the 2018-19 academic year.

"It's such an amazing opportunity, especially as an undergraduate student, to really develop the methods we want to use and have the time to build on previous work," says McGuire. "Being able to simultaneously work on those different tasks, all contributing to the same project, has been a great way to put in practice things I've learned in my math and computer science classes."

The Power of Graffiti in the Middle East

Mohan Chen '19 talks to Vickie Langohr, associate professor of political science, about her research on graffiti in the Middle East. Photo by Tom Rettig

Mohan Chen '19 talks to Vickie Langohr, associate professor of political science, about her research on graffiti in the Middle East. Photo by Tom Rettig"There is an increasing number of people in Egypt and the West Bank choosing graffiti as a political method to convey their demands to the government and international society. My research focuses on the artists' motivations and people's demands reflected in these paintings. Graffiti has played a crucial role in the Egyptian Revolution and long-lasting resistance in Palestine. Street art is like a mirror of society; we are able to see the changing events and social issues through them."

So Chen, an international student from Ningbo, China, teamed up with Langohr, scouring websites and books on graffiti to research the artists' motivations reflected in the street paintings. She's also studying the relationship between the different groups or artists and their local communities.

Langohr applauds Chen's attempt to use graffiti to tell a story of political uprising. "Political events themselves can seem quite foreign to students who have never lived in the Middle East, but seeing them rendered in graffiti, or put in a novel or a rap song, makes them seem more interesting."

As an example, Langohr cites the graffiti in Cairo following Egyptian protests. "Both before and after June 30, 2013, graffiti on major walkways was something that people of almost all social classes would see as they moved around the city, even those who were not interested in politics or didn't have the time or money to access news about politics in more formal ways such as TV or social media. Seeing pro-revolution graffiti also gave the pro-revolution passerby a sense of pride and a belief that the goals of the revolution could be achieved."

Mohan Chen '19 poses with a photo of a piece of graffiti depicting political unrest in Cairo, Egypt. Photo by Tom Rettig

Mohan Chen '19 poses with a photo of a piece of graffiti depicting political unrest in Cairo, Egypt. Photo by Tom RettigIn fact, to capture these moments in time, Chen set up a website as a kind of graffiti archive. "In addition to the website, I started an Instagram account where I post a graffito I find interesting every day. These are voices that deserve to be heard by the world."

So even when the summer comes to a close, Chen plans to continue adding photos of graffiti to the website. "The issues in Egypt and the West Bank still exist. It means there will be more people using art to communicate their ideas. I did not take this on as a short-term project."