Like many, Tim Youd '89 goes to work and types at a desk. However, the desk varies depending on the state or country he's in, and when he types, it's not on a desktop or the newest MacBook: It's on a typewriter, technology of the past that proves instrumental to his work.

He's two-thirds through his ambitious "100 Novels" project, a years long creative endeavor in which he retypes beloved, controversial and groundbreaking novels as performance art over the course of numerous days on the same model typewriters on which they were originally created. Each novel is retyped on a single sheet of paper, backed by a second sheet, which together are repeatedly run through the typewriter. By the end, one sheet is near-battered and often torn, having been typed on for hundreds of pages, and the other likely stained with ink that bled through the top page. The two are presented side by side as a diptych, mirroring an open book.

Youd has completed 65 novels and catalogs an ever-evolving database of the hundreds of books he'd be interested in tackling. The lone rule: The novel must have been written on a typewriter.

"Because I come at this from the perspective of a visual artist, what got me interested in the idea in the first place was the recognition that when you're reading a book, on a formal level you're looking at a rectangle of black text inside a larger rectangle of white," he explains. "It was that visual stimulation that led me to think about compressing all the words, almost palpably — squeezing the book into that rectangle of paper."

Youd first retyped Hunter S. Thompson's "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" in early 2013 in his Los Angeles studio. At that point, he didn't realize he had initiated what would become "100 Novels."

"Thompson had typed out 'The Sun Also Rises' and 'The Great Gatsby' because he wanted to better understand those books from the inside-out; like if you want to be an architect, you build a house," he says. "He took a hands-on approach, which I appreciate. I think with visual art and writing, there's an element of craftsmanship. You get your hands on it and those things come together and inspired my first exploration, which also obliquely connected to the fact that I'd visited some writers' houses over the years and was conversing with this idea of a literary pilgrimage."

He didn't perceive that first completion as a performance, but the work snowballed from there. After a few retypings in his studio, a coincidence jumpstarted the project a few months later.

"This gallery that showed my work early on was going to New York for an art fair, and at the same time, I was on the board of the Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur and they were heading to Brooklyn, where Miller is from," Youd says. "So I thought this would be a chance to do a retyping of a novel in the location that was significant to Miller."

The library then contacted The City Reliquary Museum in Brooklyn, and after syncing up, Youd sat outside the museum and typed Miller's "Tropic of Capricorn" on the sidewalk.

"I was there for 12 days, it's close to 350 pages," says Youd, who retypes about six pages an hour. "The first morning I had a sign saying this is what I'm doing and I'm not going to stop and talk, but after an hour or so, I took that down and allowed myself to be interrupted. People had a lot to say! I've kind of maintained that approach; generally speaking, if someone wants to talk to me, I'll stop and see what they want to say. It was my first time doing this and it was a kind of kooky environment — people would ask me for directions; I was this odd street person."

Vassar College's Miscellany News has called Youd's work "hagiography by destruction" and the Los Angeles Times remarked that it "involves drudgery, not glamour." (His endurance and devotion have further been testified to in The New York Times, Huffington Post and other prominent outlets.)

From Wall Street to LA

His craft is unique, and Youd's path toward this career has been just as singular. "I was an economics major at Holy Cross and it was the '80s. I thought Wall Street was the end goal, like Michael Douglas and Gordon Gekko," he says of the Academy Award-winning actor and the iconic role he created in Oliver Stone's 1987 movie "Wall Street." "I wanted a life of adventure and thought that's where it was. It was really hard, I learned a lot, the hours were super long, and it felt like you were almost being hazed being an associate at an investment bank, but I said I can take it. It was a young man's dream."

But soon thereafter, he relocated to Los Angeles to work in film. (He produced, among other independent films, "Garden Party," which marked Academy Award-winner Jennifer Lawrence's film debut.) "I thought I'd make movies and it'd be fast and glamorous and creative," he says. "It's not so different from those who come out of school and want to move to Silicon Valley and be the next Steve Jobs. But as I started down that path, there was a slow realization that I might be OK at film, but I'm getting less and less happy. The more I see, the less I like."

After saving money from these endeavors, including a direct marketing business, he felt it was time to start anew. And while it's been years since he's been in a Holy Cross classroom, he's still enacting the lessons he's learned in his art.

"I took a lot of English classes electively and enjoyed those most," says Youd, who grew up in Worcester. "It's where I developed my habit of reading. You don't get to Holy Cross if you can't read a book, but I developed a love of close reading."

He credits Richard Matlak, English professor emeritus, who taught him "the value of close reading. When I'm doing a performance and reading a book, I'm invested in being a good reader, so I annotate as I go," he says. "I'll be typing and stop and write a note. The books have gotten more heavily annotated as I go and I credit him. Sometimes it's a pain to stop and look up a word, but I learned that from him and I think it's been such a valuable lesson. If you really want to understand the story, you can't just gloss over a word you don't understand; pull out the dictionary or pause and see what's going on."

Distilled to its essence, Youd's art is one of devotion: not just to the performance, but to the writers he's appreciating. "I'm attempting to be a very good reader, and when we do that, we have this out-of-body experience," he explains. "If you're engrossed in something, you have this way of hovering outside of yourself, and I think that is akin to a religious ecstasy. There are renditions of saints in visual art hovering off the ground — they're reacting to reading the word of God. I think any kind of language can give us that similar out-of-body experience."

Traveling and Typing

Youd is represented by Cristin Tierney, a New York art gallery through which he recently participated in the 2020 edition of The Armory Show, the city's premier art fair. There, he retyped his 66th novel, Sylvia Plath's "The Bell Jar" on a Hermes 3000, the model on which the 1963 novel was written. (Actually, he performed with two Hermes 3000s, as one jammed halfway through the performance; he always brings a backup just in case.) While he always chooses books that appeal to him, it can involve more research to find novels not written by white men, especially when institutions value representation.

"I started to question why there weren't a lot of women or people of color on my list, and I thought for the most part publishing in the 20th century favored the white male," he notes. "But then I thought if I want to type more women or people of color or LGBTQ writers, I have to dig a little bit. Maybe they are there and were published by smaller presses.

"It's expanded my universe and the number of voices I hear in my head now," he adds. "I'm challenged by the curators, who are also thinking about these things. These people existed but they weren't written into the narrative properly. It's opened my own eyes and I feel better for that."

After selecting a novel, the performance is tied to a location significant to the book or author. He's travelled to William Faulkner's home in Oxford, Mississippi, to retype "The Sound and the Fury;" to Godrevy Lighthouse in the middle of the U.K.'s St. Ives Bay to complete Virginia Woolf's "To the Lighthouse;" and to the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library in Indianapolis during Banned Books Week for Ray Bradbury's "Fahrenheit 451." The completed diptychs are often sold upon completion, but in keeping with the theme of Banned Books Week, Youd burned the retyped "Fahrenheit 451" when he finished. (That didn't stop his audience from scooping up the ashes.)

Other performances have been held in settings ranging from a decommissioned guard tower in New York's maximum security Sing Sing prison (John Cheever's "Falconer") and Venice's Grand Canal (Patricia Highsmith's "Those Who Walk Away") to under an oak tree on Louisiana Highway 416 (Ernest Gaines' "The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman") and the Santa Monica Pier (Raymond Chandler's "Farewell My Lovely").

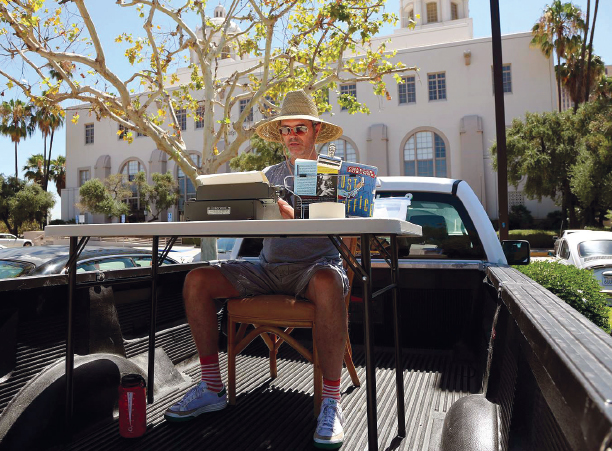

Given this range, Youd admits it's hard to pick a favorite performance site, but he can pinpoint a seminal one: "As only my second public performance, I retyped Charles Bukowski's 'Post Office' in the parking lot of the Los Angeles Terminal Annex Post Office in July 2013," he says. "Bukowski worked at this post office for 14 years, quit and then immediately wrote this novel, which was his first. For this piece, I rented a pickup and every day paid $5 to park in the lot. I set a table up in the bed of the truck and sat there typing in the blazing summer sun for a week. It turned out the LA Times' lead art critic, Christopher Knight, liked what I was doing and wrote a highly positive feature review, which led to my first museum shows at the Lancaster Museum of Art and History and the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego."

He recalls retyping a novel at the Lehman Loeb Art Center in New York's Hudson Valley a year or so ago. In the throes of his retyping — reading the text, pressing on the typewriter's keys, darkening the ink-stained page before him — "someone observed me and said it was like I was eating the book," he laughs.

Youd believes it will take 12-14 years to complete "100 Novels," making it one of the longer occupations he's had in his storied career. "It's been a lot of fun; I've certainly never been happier doing anything for an extended period of time," he notes.

Written by Billy McEntee for the Spring 2020 issue of Holy Cross Magazine.

About Holy Cross Magazine

Holy Cross Magazine (HCM) is the quarterly alumni publication of the College of the Holy Cross. The award-winning publication is mailed to alumni and friends of the College and includes intriguing profiles, make-you-think features, alumni news, exclusive photos and more. Visit magazine.holycross.edu/about to contact HCM, submit alumni class notes, milestones, or letters to the editor.